In late February, Blue Origin plans to fly New Glenn again — this time carrying AST SpaceMobile’s BlueBird 7. The satellite is built to talk to ordinary smartphones, not dishes or special handsets. The launch is a test of whether “direct-to-device” connectivity can become a real service, rather than a clever demo.

In most countries, mobile coverage is now a solved problem — until it isn’t. Step into a national park, cross a mountain pass, drive long enough through desert, or watch a storm take out a tower. Suddenly, the modern phone becomes a glass rectangle again.

Mobile operators have spent decades filling these gaps, but the economics get ugly at the edges. One US carrier says more than 500,000 square miles of the country are not covered by any wireless company’s towers — a marketing statistic, yes, but it captures the underlying truth: some places will always be too expensive, too remote, or too fragile for perfect terrestrial coverage.

That is the space where the satellite-to-smartphone race is trying to land. Not as a replacement for 4G and 5G networks in cities, but as a new “last layer” — a backstop for emergencies, a bridge for rural users, and a resilience tool for first responders and critical infrastructure.

The next big marker comes in late February 2026, when Blue Origin says New Glenn-3 will carry AST SpaceMobile’s BlueBird 7 into low Earth orbit from Cape Canaveral.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy BlueBird 7 matters

Direct-to-device is often described as “cell towers in space”. The phrase is useful — and misleading.

It is useful because the goal is familiar: your phone connects without extra hardware, without a specialised satellite handset, and (ideally) without changing how you use apps. It is misleading because the physics are brutal. A smartphone has a small antenna and limited power. The signal has to travel hundreds of kilometres, cut through atmosphere, and compete with interference. If the satellite is small too, the link simply does not close for broadband.

AST’s answer is not subtle: build big.

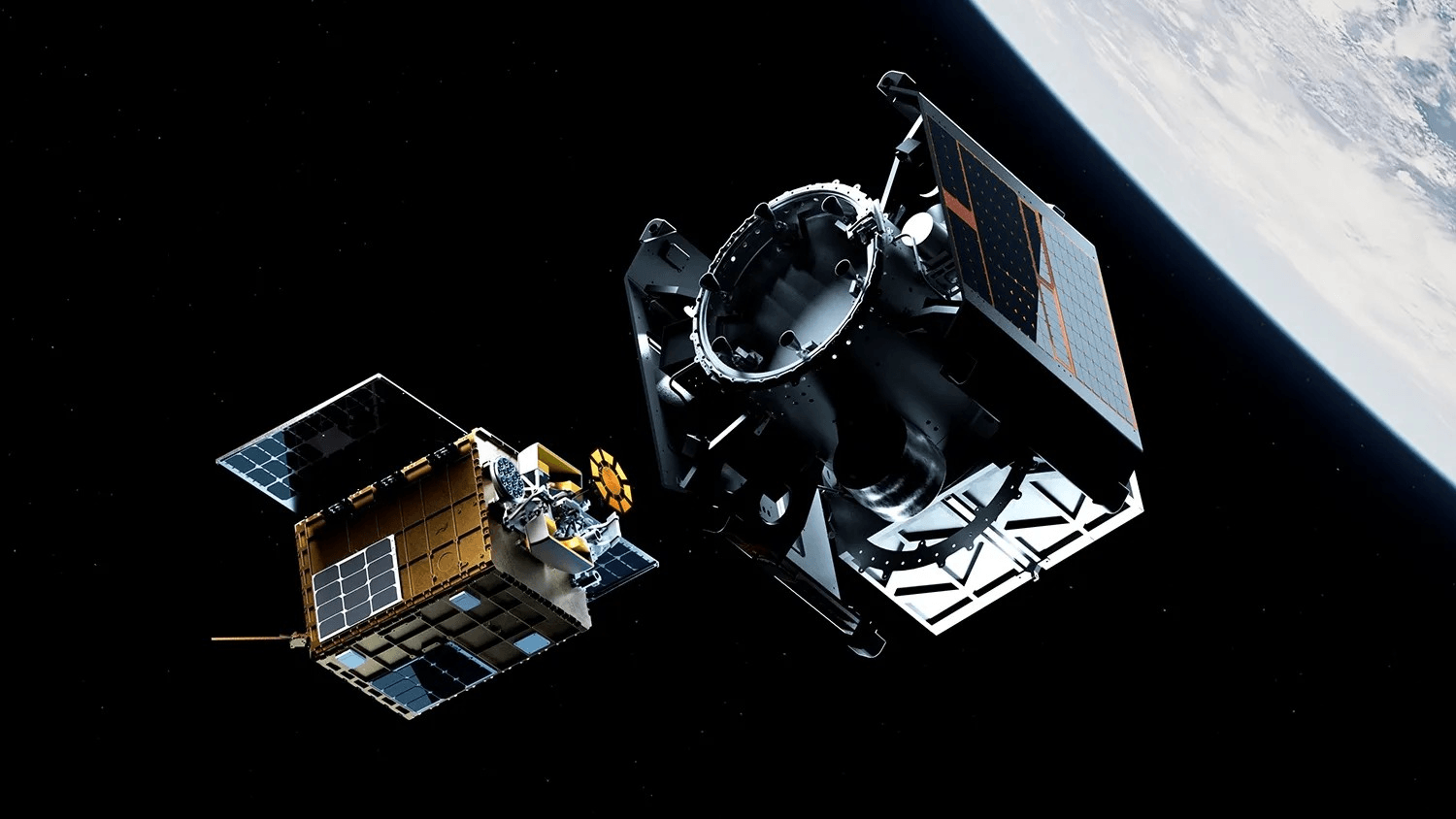

In a Business Wire release, AST says BlueBird 7 is identical to BlueBird 6, with a communications array of nearly 2,400 square feet — “the largest commercial communications array in low Earth orbit” — and claims peak data rates up to 120 Mbps for voice, data and streaming.

It is hard to overstate what that means in practical terms. BlueBird 6 — launched on December 23, 2025 on India’s LVM3 rocket — is reported to weigh roughly 6,100kg and deploys a phased-array surface far larger than the earlier BlueBird satellites.

This is the strategic wager: fewer, much larger satellites that can deliver higher-capacity links directly to everyday phones, rather than thousands of smaller satellites that start with basic messaging and gradually add limited data.

AST’s own language is ambitious. But the immediate point is more concrete: a second next-generation satellite in orbit is another datapoint for performance — and a prerequisite for offering anything more than trials.

The rocket is part of the story

The other reason BlueBird 7 matters is the vehicle underneath it.

AST says the mission is its first launch with New Glenn, and it highlights the rocket’s seven-metre fairing, which it says can enable up to eight Block 2 BlueBirds per mission — roughly double the payload volume of typical five-metre-class commercial fairings.

That capacity number shows up in industry reporting too: AST has said New Glenn can take up to eight BlueBird satellites, while a Falcon 9 can carry up to three of the next-generation birds.

For Blue Origin, New Glenn-3 is also about credibility and cadence. The company says NG-3 follows a successful NG-2 mission and will reuse the same booster, now being refurbished. The booster landing on NG-2 was a public milestone: Blue Origin’s mission page says NG-2 flew on November 13, 2025, deployed NASA’s ESCAPADE spacecraft, and landed the first stage on its ocean platform, “Jacklyn”. (Its first mission, NG-1, reached orbit on January 16, 2025, also from LC-36. )

Put simply: AST needs a high-volume launch option for a bulky satellite, and Blue Origin needs customers that justify flying more often. The partnership is a neat fit — on paper.

“Intermittent” first, “continuous” later

The most important word in early direct-to-device rollouts is not “broadband”. It is “intermittent”.

AST’s plan for 2026 is aggressive. It says it expects one orbital launch every one to two months on average during 2026, and it is “on track” to launch **45–60 satellites by the end of the year”.

That cadence matters because continuous coverage is a geometry problem. You need enough satellites in enough orbital planes so that, at any given moment, one is above your horizon with a usable link.

In November 2025, Light Reading reported AST’s own view of the ramp: the company expected “intermittent nationwide” service in selected markets in early 2026, with “continuous” service later in 2026 as more satellites are added. It said a non-continuous service could be achieved with an initial constellation of 25 satellites (five earlier Block 1 spacecraft and 20 Block 2), while 45–60 satellites would enable continuous service in major markets.

This is a sensible sequencing. Most consumers will not tolerate a patchy replacement for 4G. But they will accept an intermittent safety net: a service that works when nothing else does, and that gets better over time.

The practical constraint is execution. Light Reading reported that AST had built 19 satellites and expected to have built 40 by around the end of March 2026, aligning manufacturing with its planned launch campaign.

Hardware, in other words, is no longer the only challenge. Operations is.

The real customer is the mobile operator — and the public-safety agency

One easy way to misunderstand the direct-to-device market is to treat it like consumer satellite internet. The early winners are not likely to be the companies that sell a new gadget to end-users. They are likely to be the companies that become part of the existing mobile network.

In the US, the carrier partnerships are now moving into pre-commercial phases. AT&T has said it plans to start offering a “beta” direct-to-device service in the first half of 2026 to a select group of consumers and FirstNet public safety users, with commercial launch to follow.

The detail that matters is not the press headline, but the plumbing. AT&T described ground “gateways” that connect the satellites to its terrestrial network — and noted that more are needed to support commercial service across the US.

Verizon, meanwhile, signed a definitive commercial agreement with AST in late 2025. Light Reading reported that the deal expanded an earlier agreement that included a $100mn investment and contribution of 850MHz spectrum — the kind of low-band frequency that travels further and penetrates better, and therefore matters disproportionately for rural coverage.

This is what “going real” looks like: spectrum, gateways, network integration, and product decisions about who gets the service first (public safety is an obvious early constituency).

Starlink is already shipping — but it is a different product

AST is not racing an empty track. Starlink’s advantage is scale, and it is using it.

T-Mobile markets its satellite product as being powered by 650+ Starlink “Direct to Cell” satellites and supports “texting & select satellite-ready apps” in outdoor areas where users can see the sky. It also adds a caveat that will become familiar in this category: data speeds are limited, performance varies, and there may be short gaps as satellites move overhead.

That is a very different value proposition from AST’s “broadband-to-phone” ambition. It is closer to a reliable, mass-market messaging and light-data layer — which is arguably the smarter first step.

This is also where Starlink’s regulatory momentum matters. On January 9, 2026, Reuters reported that the FCC approved SpaceX’s request to deploy 7,500 additional second-generation Starlink satellites, bringing its approved total to 15,000. Reuters added that Starlink already operates a network of about 9,400 satellites.

If you are trying to deliver continuous service, constellation scale is a weapon. It is also a set of costs and risks — congestion, collision avoidance, spectrum fights — that smaller constellations can sometimes avoid. But the immediate commercial truth is blunt: Starlink’s direct-to-cell services can be shipped earlier because the satellites are already there.

Light Reading put the competitive angle plainly: AT&T and Verizon are “behind” T-Mobile in US direct-to-device services, and T-Mobile has made its service available even to customers of other networks.

The market is, in effect, running two experiments at once:

- one, a high-scale “good enough” service that starts with messaging and small amounts of data;

- two, a lower-satellite-count approach that tries to leap closer to broadband by building enormous spacecraft.

BlueBird 7 sits in the second experiment.

The hardest problem is not in orbit — it is on the ground

A useful mental model is to treat direct-to-device satellite coverage as a new roaming layer. Your phone will still prefer terrestrial towers. But when towers disappear, the phone needs to connect to a satellite using spectrum the mobile operator already holds, without causing interference, and without breaking the rules of national licensing.

This is where regulators are quietly doing the heavy lifting.

In the UK, Ofcom set out decisions to authorise the use of mobile operators’ spectrum bands for satellite direct-to-device services, including a framework that requires licence variations and technical conditions to manage coexistence and interference.

It is not hard to see the broader implication: direct-to-device will expand fastest in countries that can reconcile three things quickly — spectrum rights, interference protection, and accountability for emergency access. The technology can be global. The permissions are national.

The business question: what is a dead zone worth?

The promise of direct-to-device can be stated in one sentence: your phone works in more places.

The problem is that consumer willingness to pay is not linear. People might pay a little for peace of mind, or pay a lot if their job depends on connectivity, or pay nothing if the service is too intermittent to trust. Operators, meanwhile, want differentiation — but not at the cost of sacrificing scarce spectrum or taking on open-ended regulatory risk.

Industry research has tended to frame the opportunity as incremental — and largely wholesale. A GSMA Intelligence overview of the category argues that direct-to-device can help telcos “chip away” at coverage gaps and suggests an incremental revenue opportunity for operators of over $30bn by 2035, with wholesale partnerships the most likely revenue model.

That framing matters because it brings the conversation down to earth. If direct-to-device is mainly wholesale, then the winners will be the firms that can integrate smoothly with mobile networks, prove reliability for emergency use, and deliver a cost per megabyte that does not frighten carriers.

In that light, AST’s bet on fewer, larger satellites becomes clearer. If each satellite can deliver higher capacity, you might need fewer of them for a service that carriers can brand and price. But those satellites are heavy, complex and expensive — and the launch campaign must be executed with industrial discipline.

A late-February launch, and a 2026 verdict

So what will BlueBird 7 actually prove?

Not that satellites can replace towers. They cannot. Physics wins.

But it can prove three things that matter more:

- that a truly standard smartphone can maintain a usable broadband-grade link to a spacecraft with no extra hardware;

- that a new heavy-lift rocket can fly, land, and fly again on a cadence that supports constellation build-out;

- that the bottleneck has shifted from “can we do it?” to “can we operate it?” — spectrum permissions, ground gateways, carrier products, and the unglamorous work of making a new network behave like an old one.

A decade ago, satellite-to-phone looked like a niche. In 2026, it is starting to look like a feature the public will simply expect — like WiFi calling or eSIM — especially after the first time it saves someone in a blackout, a wildfire, or a flood.

The uncomfortable question for the industry is not whether it will work. It is whether it will work well enough, cheaply enough, and legally enough to become boring. BlueBird 7’s job is to make that future feel less like a concept deck — and more like a launch manifest.