In the space business, annual launch totals have become a kind of heartbeat. In 2025, China’s pulse quickened.

Tracking data compiled by Space Stats Online shows 93 Chinese orbital launches in 2025, up from 68 in 2024 — a jump of roughly 37% in a single year. The world logged 324 orbital launches in total, meaning China accounted for about 29% of global activity by that measure.

That is not “SpaceX-level” yet — but it is no longer a sideline, either. A country that can put something in orbit roughly every four days has moved from aspiration to execution.

The deeper question is what this faster tempo is for. The answer is not one big mission, but thousands of small ones: the build-out of megaconstellations in low Earth orbit (LEO), designed to deliver broadband and secure communications — and, in practice, to stake a claim on two scarce resources that are hard to see from the ground: orbital real estate and radio spectrum.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe numbers tell you “how fast”; the constellations tell you “why”

China’s 2025 increase looks closely tied to constellation deployment. Analysts tracking launches point to two headline projects:

- Guowang (“national network”), operated by the state-run China SatNet, widely described as targeting ~13,000 satellites in its mature form.

- Qianfan (“Thousand Sails”), linked to Shanghai-backed SpaceSail/SSST, which Reuters has reported aims for more than 15,000 satellites by 2030, with 648 satellites targeted by the end of 2025 (at least as a stated milestone).

Add in other announced efforts — including Geely-backed Geespace, which has spoken about eventually building a constellation numbering in the thousands — and a pattern emerges: China is not building a satellite network; it is building an ecosystem of networks, some state-led, some commercially packaged, all politically meaningful.

This matters because LEO is not infinite. It feels infinite when you look up at the night sky. It does not feel infinite when you are trying to keep thousands of fast-moving objects from colliding, while also keeping hundreds of thousands of radio links from interfering with each other.

LEO has two choke points: physics, and paperwork

Start with the paperwork — because it quietly shapes the physics.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) has, over the past few years, pushed satellite operators toward “use it or lose it” behaviour. Under milestone rules adopted for certain non-geostationary (NGSO) systems, operators must deploy 10% of a constellation within two years, 50% within five years, and 100% within seven years (counted from the end of the relevant regulatory period). The point is to discourage “spectrum warehousing” — filing for vast networks you never build.

But rules designed to prevent hoarding can also reward speed over elegance. If your deadline is measured in years, not decades, “perfect” can become the enemy of “in orbit”. That helps explain why early constellation batches often look uneven: mixed suppliers, mixed performance, evolving designs.

Now add the physics.

The European Space Agency’s latest space environment reporting notes that about 40,000 objects are tracked in orbit, of which around 11,000 are active payloads. In other words: most things up there are either dead hardware or debris, and the live population is already large — before the next wave of deployments hits.

This is where the megaconstellation era becomes less like “more satellites” and more like “a different kind of traffic”.

- Constellations cluster into similar altitude “bands” because those bands make engineering sense (latency, coverage, drag, radiation exposure).

- Many also want similar inclinations for global coverage.

- That concentrates objects into shared corridors, where close approaches become routine and collision-avoidance becomes a daily operational task.

As one blunt reality check: the business model for broadband constellations depends on scale. But scale changes the operating environment for everyone — including the operators themselves.

The comparison everyone makes — and the one that matters more

It is tempting to frame China’s surge as a simple “race with SpaceX”. There is some truth in that. SpaceX’s 2025 cadence was extraordinary: Space.com reports 165 orbital launches that Ryear, with Starlink dominating the manifest and pushing the active constellation to more than 9,300 satellites.

But the more important comparison is not a country-versus-company chart. It is a comparison of systems:

- SpaceX has made reusability into a high-tempo production line.

- China has built a high-tempo launch programme that is still, in key areas, learning reusability — while trying to deploy networks that assume industrial-scale launch.

In other words: China is pushing up against a constraint that is not purely financial. It is throughput.

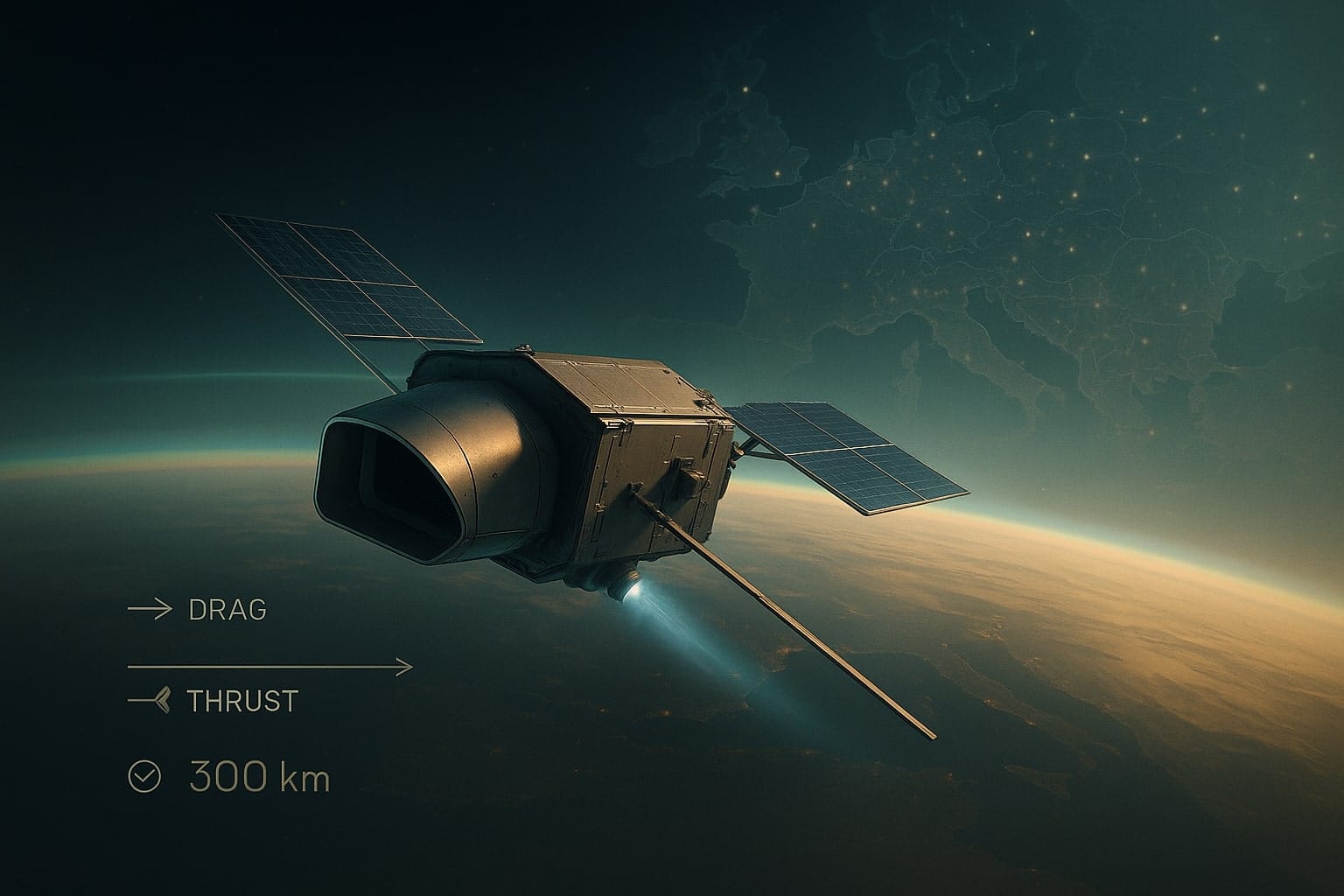

Reusability is not just about cost — it is about capacity

The megaconstellation era changes the meaning of “cheap launch”. It is not only “lower cost per kilogram”; it is “more missions without building a new rocket every time”.

China is clearly trying to close that gap.

- Reuters reported in December that private launch company LandSpace failed to complete a controlled landing during a Zhuque-3 recovery test, but aims to achieve a successful booster recovery by mid-2026.

- In early February, Reuters also reported China launched a reusable experimental spacecraft for the fourth time since 2020, after previous missions that included long-duration stays in orbit.

- And Space.com reported that China recently tested a next-generation crew capsule escape system and, in the same campaign, carried out a controlled splashdown of a Long March 10 first stage — a hint of how state programmes can also feed the reusability learning curve.

These are different categories of “reusable” — but they reflect the same strategic logic: the country wants to move from “launching often” to “launching often without rebuilding everything”.

For constellations, that shift is decisive. If you cannot recycle hardware, you must compensate with factories, engines, pads, shipping, workforce — and you will eventually find the bottleneck, because supply chains are not as frictionless as PowerPoint.

The geopolitical layer: why LEO broadband is more than broadband

There is also a reason China is willing to push so hard.

Broadband constellations are becoming national infrastructure. They shape:

- Resilience (communications that do not rely on vulnerable terrestrial chokepoints),

- Reach (connectivity for remote regions, maritime routes, and partner countries),

- Rules (who sets standards on encryption, routing, lawful access, and service terms),

- and, inevitably, leverage (because connectivity is never just a commodity).

Reuters has described Chinese rivals, including SpaceSail, expanding outreach via agreements abroad, while China’s broader ambition — as reported — could involve deploying tens of thousands of LEO satellites across projects.

Seen this way, the rush is not simply about catching Starlink. It is about avoiding a future where one country’s private network becomes the default layer for global connectivity — and where “who owns the constellation” quietly shapes “who writes the playbook”.

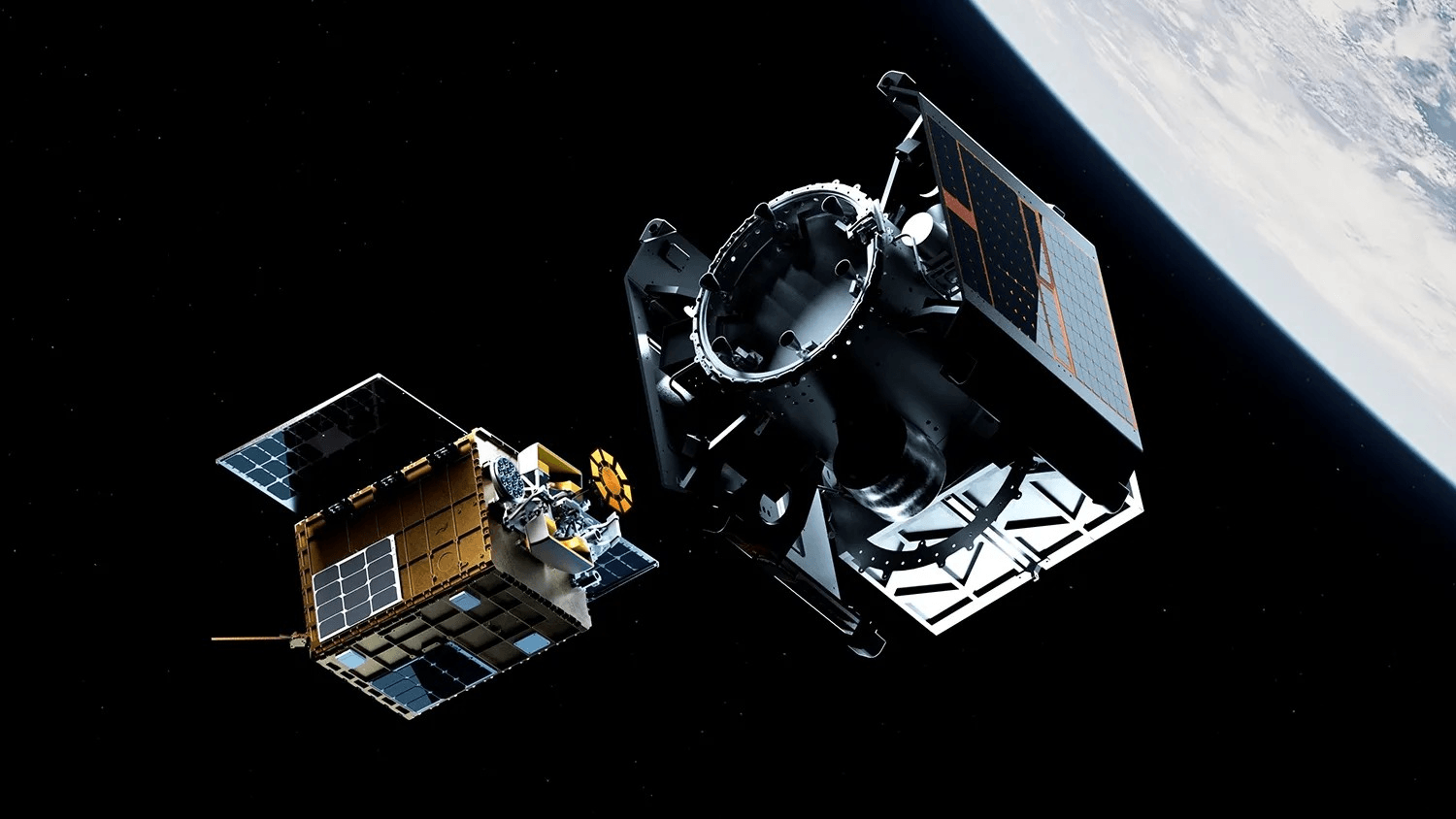

The squeeze: when everyone arrives in orbit at once

Here is the uncomfortable point the industry often dances around: LEO is a shared environment, but it is not governed like one.

Operators already coordinate. They share conjunction warnings. They negotiate spectrum coordination. But the megaconstellation era makes informal coordination feel increasingly fragile.

The stress shows up in three places:

- Collision risk and debris growth

Even with responsible behaviour, more objects means more close approaches. Failure modes also multiply: dead satellites that cannot manoeuvre, fragmentation events, or simple operational errors. Debris does not respect national flags. - Spectrum interference and “regulatory timing games”

ITU milestones are meant to stop spectrum warehousing. But they also encourage “minimum viable deployment” strategies designed to meet deadlines. That can create more satellites earlier — which is the opposite of what you would design if your only goal was clean, efficient, long-lived infrastructure. - Altitude migration and “orbital musical chairs”

When one constellation shifts shells (for safety, latency, or regulatory reasons), it changes the density profile for others. LEO becomes less like property lines and more like traffic lanes that keep moving.

None of this is a “China problem”. China is simply arriving at the moment when these systems become crowded — and bringing the scale (and state backing) to make that crowding obvious.

What happens next: a governance test disguised as a launch race

If you want a simple takeaway, it is this:

The next stage of the space economy will be constrained less by how many rockets you can build, and more by how well you can share an environment.

China’s 2025 tempo is a signal that the megaconstellation era is not theoretical any more. It is industrial. And industrial systems, once in motion, are hard to slow down.

That leaves governments and regulators with a narrow window to raise the quality of the rules — not to stop constellations, but to make them sustainable. That likely means:

- clearer, enforceable debris-mitigation and end-of-life standards,

- more transparent space traffic coordination,

- better incentives for lower-risk orbits and faster disposal of failures,

- and spectrum processes that reward real deployment without turning deadlines into a launch-at-any-cost trigger.

In the end, the question is not whether China can launch more. It almost certainly can.

The question is whether the world can build the norms — technical and political — that keep a fast, crowded orbit from turning into a slow-motion accident.