Not long ago, China’s space exploits were solely the domain of state-run behemoths. That’s changing fast. A new wave of privately funded Chinese rocket companies has burst onto the scene, echoing the entrepreneurial energy that SpaceX and Blue Origin brought to America’s space industry. Beijing’s ambitions in space have always been bold – President Xi Jinping has declared China’s “Space Dream” is to overtake all nations and become the leading space power by 2045– but now a dynamic private sector is emerging as a force multiplier. This isn’t just a matter of national pride or scientific curiosity. It signals a tectonic shift in the global space industry, one that could reshape who builds rockets, how we access space, and who sets the rules beyond Earth.

A private Chinese rocket lifts off: LandSpace’s Zhuque-2 leaping skyward from the Jiuquan launch center on July 12, 2023, becoming the world’s first methane-fueled rocket to reach orbit. This milestone put China ahead of U.S. giants SpaceX and Blue Origin in at least one cutting-edge rocket technology. It’s a striking symbol of how far China’s nascent private space firms have come in just a few years. A decade ago, the notion of Chinese startups building reusable rockets or satellite constellations might have sounded far-fetched. Today, those startups are not only real – they’re lofting satellites, attracting major investment, and plotting courses to the Moon and beyond. The rise of China’s private space sector is no longer a future prediction; it’s here, and it’s poised to upend the balance of the $400+ billion global space economy.

Table of Contents

ToggleFrom State Monopoly to Startup Boom

For most of the space age, China’s activities were the realm of monolithic state enterprises. Launch vehicles and satellites came from state-owned giants like CASC and CASIC, with no room for private players. That began to change in 2014, when the Chinese government issued a landmark policy (State Council Document 60) effectively opening the space sector to private investment. At first, progress was slow and cautious – only a handful of commercial space companies were founded in 2015-2016 amid uncertainty over how far this liberalization would really go. But within a few years, confidence grew and the floodgates opened. From basically zero private space companies in 2014, China now has more than 200 commercial space firms in operation. In other words, an entire ecosystem of space startups has materialized in the span of one decade, marking one of the most rapid industry expansions ever seen in the global space arena.

The numbers behind this boom are telling. By 2021, Chinese commercial space startups had raised an estimated ¥33 billion (around $5 billion USD) in cumulative investment– a figure that was virtually nil prior to 2014. Annual investment peaked around 2020, with over ¥9 billion (~$1.5 billion) poured into these companies in that single year. And the momentum continues. The Chinese government itself has dramatically ramped up spending on space, signaling strong support for both state and private programs. Beijing’s space budget skyrocketed from about $2.2 billion in 2022 to $14.5 billion in 2023, a more than six-fold surge in one year. While that’s still less than NASA’s ~$25 billion annual budget, it underscores how serious China is about funding its space ambitions. This influx of capital – from venture investors, tech giants, and government coffers alike – is fueling an entrepreneurial fervor reminiscent of Silicon Valley, but with Chinese characteristics.

Crucially, Beijing has not left this “space gold rush” to chance. In late 2023, China’s central government designated commercial space as a strategic emerging industry for the first time, weaving it into the nation’s official development priorities. At the same time, provinces and major cities are competing to incubate local space champions. Regional authorities in places like Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Guangdong are rolling out tax breaks, subsidies, industrial parks and even dedicated spaceports to attract space startups. This decentralized push has led to the rise of space industry clusters across China – more than ten new space industrial parks have sprung up in the past 5–7 years. The result is a unique hybrid model: private companies pursuing profit and innovation, yet often receiving hefty state support and leveraging state-developed infrastructure. It’s capitalism, but still very much guided by government policy – a “commercial space sector with Chinese characteristics,” as analysts have dubbed it.

China’s SpaceX Moment – Meet the New Rocket Players

In the West, names like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Rocket Lab have become synonymous with the private space revolution. Now China has its own cadre of scrappy upstarts, and they are quickly making a name for themselves. Where these Chinese firms were once dismissed as mere copycats, they are now hitting milestones that even the U.S. giants envy. The Zhuque-2 rocket launch by LandSpace in 2023 is one example – beating SpaceX and Blue Origin to demonstrate a methane-fueled orbital rocket– but it’s far from the only one. To get a sense of this new landscape, consider a few of China’s emerging space companies and how they stack up against their Western counterparts:

- LandSpace – Founded in 2015, LandSpace was one of China’s first private launch startups and is often likened to a Chinese version of SpaceX. The company developed the Zhuque-2 medium-class rocket, which in July 2023 became the first-ever methane/liquid-oxygen launch vehicle to reach orbit. LandSpace is now working on reusable rockets to compete globally– much like SpaceX drove reusability with its Falcon 9. In many ways, LandSpace’s rapid progress (from zero to orbit-capable methane rockets in under 8 years) exemplifies China’s fast-follower approach to space tech, adapting cutting-edge ideas at breakneck speed.

- iSpace – A Beijing-based startup and a pioneer in China’s commercial space sector, iSpace made history in 2019 by becoming the first private Chinese firm to reach orbit with its Hyperbola-1 rocket. That modest solid-fueled rocket launch – lofting a small satellite into low Earth orbit – was China’s “SpaceX moment,” demonstrating that startups could do what previously only national agencies accomplished. iSpace has hit some snags since (a few high-profile launch failures), but it’s now developing a larger reusable launch vehicle to get back in the game. The very idea of a reusable Chinese rocket was unthinkable a decade ago; iSpace aims to make it routine.

- Galactic Energy – Founded in 2018, Galactic Energy is another rising star. It built a solid-fuel rocket called Ceres-1 that has already completed multiple successful orbital launches, delivering commercial payloads for paying customers. With those under its belt, Galactic Energy is moving on to Pallas-1, a larger liquid-fueled rocket designed for reusability. The firm raised over $200 million in recent funding rounds to support this effort. If all goes well, Pallas-1 could become China’s equivalent to SpaceX’s Falcon 9 – a workhorse booster that can be flown multiple times, drastically lowering costs.

- Space Pioneer (Tianbing) – A newcomer that has quickly leapt to the front of the pack. Space Pioneer, founded in 2019 by alumni of LandSpace, achieved a major feat in April 2023: it successfully launched its Tianlong-2 rocket on the first attempt, making it the first Chinese startup to reach orbit with a liquid-fueled rocket. This 3-stage rocket carried a pair of satellites for a commercial client, proving the viability of privately-developed kerosene engines. Notably, Space Pioneer didn’t do it all alone – it procured some key components from state-owned suppliers (its first stage engines were bought from a CASC subsidiary). This highlights a unique advantage for Chinese firms: they can lean on an established domestic supply chain for rocket parts, a legacy of the state program. With that boost, Space Pioneer pulled off in 4 years what took SpaceX six or seven.

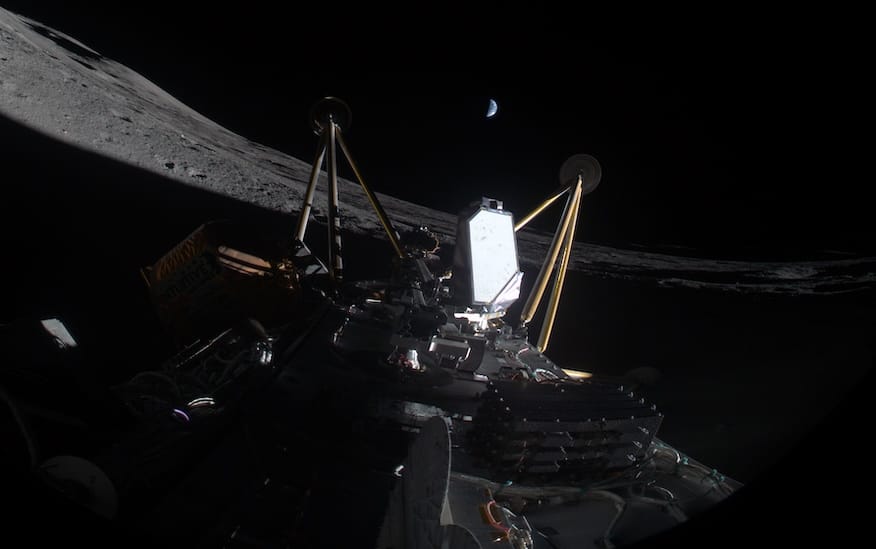

- Deep Blue Aerospace – Often compared to SpaceX in terms of ambition, Deep Blue is laser-focused on reusable rocket technology. In 2021 and 2022 the company performed a series of vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) tests, launching a small prototype rocket and then landing it softly back on Earth – a trick pioneered by SpaceX’s Falcon boosters. In one dramatic September 2024 test in the Gobi Desert, Deep Blue’s Nebula-1 demonstrator flew to several kilometers altitude and descended gently to a pad, guided by its rocket engines. The image of a cylindrical booster hovering and landing under rocket thrust – once unique to SpaceX – is now also a scene from the Chinese desert. Deep Blue’s planned full-scale rocket could become China’s first reusable orbital launcher, aiming to further drive down launch costs.

These are just a few of the more prominent players. There are dozens of others: OneSpace and LinkSpace (early entrants in small rockets), CAS Space (a spinoff backed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences), satellite makers like CGSTL (Changguang Satellite) in remote sensing and GalaxySpace in broadband communications, to name a handful. The sheer breadth of China’s space startup scene is remarkable – from launch vehicles to satellite constellations to space robotics – and new firms are still popping up each year. As one space analyst quipped, when it comes to commercial space, “Made in China” is likely to become a commonly heard phrase in the space sector.

It’s worth noting that China is not the only nation trying to replicate the SpaceX formula. For instance, Britain is also nurturing a nascent private space industry. Homegrown UK startups like Skyrora and Orbex are developing small orbital rockets, with plans to launch from Scottish spaceports in the next couple of years. The UK government and ESA have injected funding to help these “Britain’s SpaceX” projects get off the ground. However, unlike China’s startups, none of the UK’s contenders have reached orbit yet. Orbex is targeting a maiden flight in 2025 and Skyrora is aiming for a debut from Shetland soon, but these timelines have a way of slipping. The contrast is striking: fifty years after Britain’s first and only orbital launch (Black Arrow in 1971), the UK is still gearing up for a comeback, whereas Chinese private companies – essentially nonexistent a decade ago – are already launching payloads regularly. In the new space race, China’s commercial sector has moved from zero to neck-and-neck with the West in record time.

Big Money, Big Dreazms – and New Technology

China’s private space surge isn’t just about counting rockets; it’s also about the money and innovation propelling those rockets. Beijing’s bet is that fostering a commercial space economy will unlock greater creativity and efficiency, much as SpaceX revolutionized rocketry in the U.S. So far, the bet seems to be paying off. Private capital is flooding into Chinese space firms, and technological milestones are piling up. If you follow the money, you can see why China’s upstarts are poised to challenge the old order of Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and other legacy players.

First, the investments: Since 2014, well over $6 billion has been invested into Chinese commercial space companies, and the pace is accelerating. Even through the pandemic years, new funding rounds continued. In fact, 2020 saw a record ¥9+ billion (~$1.5 billion) of private investment in China’s space startups– an astonishing figure, equivalent to the entire annual budget of some national space agencies. And while global venture funding cooled in 2022–23, Chinese space firms still attracted large sums. Late-stage startups like Galactic Energy and LandSpace have reached “unicorn” status (valuations around or above $1 billion) on the back of successive funding rounds. For example, Galactic Energy raised ¥1.27 billion (~$200 million) in late 2021 and another $150+ million in 2022 for its reusable rocket program. LandSpace similarly secured around ¥500 million (~$71 million) in Series C funding to push Zhuque-2 toward commercialization. These amounts, while smaller than SpaceX’s multi-billion-dollar war chest, are unprecedented for Chinese startups – and they are backed by an ecosystem of venture capital firms, tech conglomerates, and even local governments eager to have a stake in the “space rush.”

All this capital is chasing a tantalizing prize: a share of what many predict will be an enormous future space market. Morgan Stanley famously projects the global space economy could grow from ~$350 billion today to over $1 trillion by 2040, driven by satellite internet, space tourism, and more. China clearly wants a big slice of that pie. One Chinese industry forecast suggests the country’s own aerospace and commercial space market could be worth $900 billion by 2029 (though definitions vary, and that figure likely includes aviation). The exact numbers matter less than the trend: investors see space as the next high-growth sector, and they view China’s startups as prime vehicles (quite literally) to capture that growth. It’s telling that even Chinese internet companies like Tencent and Alibaba have quietly backed space ventures, diversifying into the final frontier.

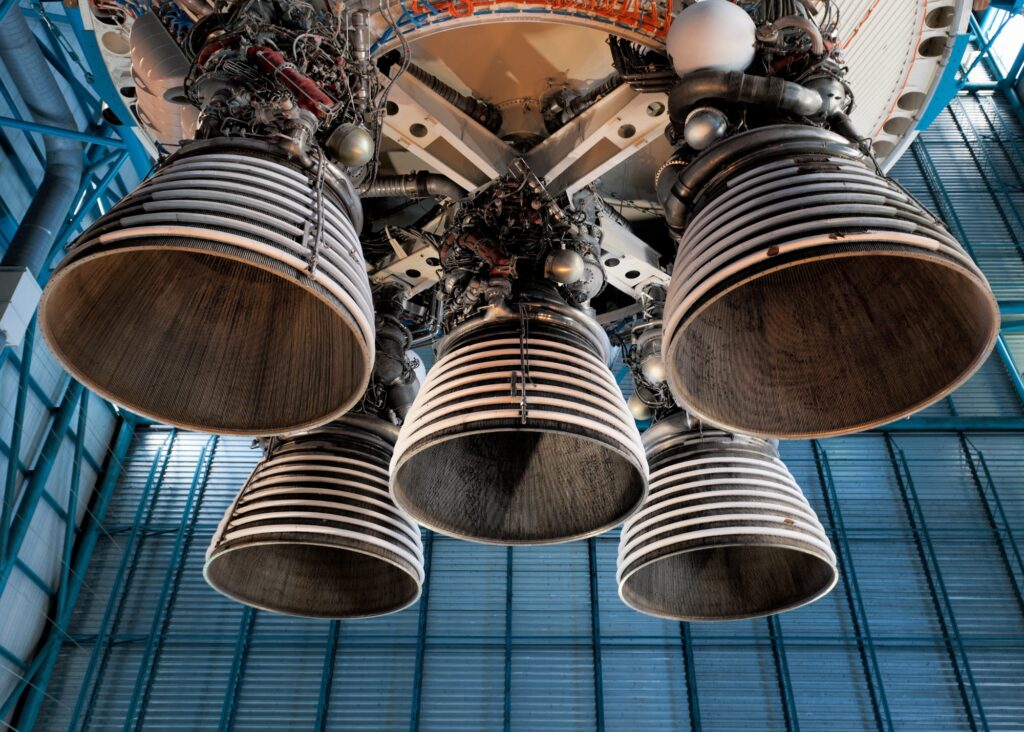

What are Chinese companies doing with this influx of funds? Developing new technology at a blistering pace. Take rocket engines – long a sticking point in rocketry. In the 2000s and 2010s, American startups reinvented the craft with innovations like SpaceX’s Merlin and Raptor engines or Blue Origin’s 3D-printed BE-4, leaping ahead in propulsion tech. Now Chinese firms are closing that gap. LandSpace’s engineers designed the “Tianque-12” methane/liquid oxygen engine that powers the Zhuque-2 rocket, making China only the third country (after the US and Russia) with a private firm developing methane-fueled rocket engines. Methane rockets are considered next-generation because they can enable cleaner, potentially reusable launches – SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s forthcoming New Glenn both use methane fuel. So when LandSpace beat SpaceX to an orbital methane rocket launch in 2023, it sent a clear message: Chinese startups can push the envelope, not just follow in others’ footsteps.

Reusability is another case in point. SpaceX turned heads by landing Falcon 9 boosters; now Chinese companies are all racing to make their rockets reusable as well. Deep Blue Aerospace’s successful hop-and-land tests showed that the basic mechanics of propulsive landing are within China’s grasp. LinkSpace (a small startup) was an early mover too, achieving a low-altitude rocket hover test back in 2019. And virtually every serious Chinese launch firm – from iSpace to Galactic Energy – has designs for reusable models in the works. These range from powered vertical landings to parachute recovery systems. It’s a dramatic shift from just a few years ago, when even China’s state rockets were all single-use. The learning curve is steep, and it’s likely some Chinese boosters will explode during landing attempts (just as SpaceX had its early crash landings). But given the technical strides made so far, few doubt that by the late 2020s China will have its own fleet of reusable orbital rockets, drastically lowering launch costs for both domestic and international customers.

Satellites and mega-constellations are a big part of the picture too. SpaceX has Starlink, Amazon is developing Kuiper – and China is gearing up to deploy its answer to these broadband constellations. A state-owned enterprise called China SatNet (China Satellite Network Group) has plans to launch a network of 13,000+ internet satellites (some reports say up to 26,000) over the next several years. While SatNet is government-led, it will rely on the capacity provided by the commercial launch sector– meaning many of those thousands of satellites could ride to orbit on private rockets like Galactic Energy’s or CAS Space’s. Already, a private firm GalaxySpace has launched an experimental batch of 5G broadband satellites (dubbed the “Mini-Spider Constellation”) to test technologies for a future internet constellation. If China proceeds with a full Starlink-rival network, it will generate huge demand for launches (one estimate suggests launching an average of 7 satellites per day through 2030 to pull it off). This could be a boon for Chinese launch startups – a massive home market to service – and at the same time create a parallel satellite internet system in competition with SpaceX’s Starlink. The technological implications are significant: more advanced satellites, innovations in mass production, and perhaps breakthroughs in laser communications or anti-jamming for these megaconstellations, given the geopolitical sensitivities.

China’s burgeoning private sector is also fostering a new generation of space engineers and entrepreneurs who think outside the traditional state-program box. They’re experimenting with 3D-printed rocket parts, AI-based satellite design, and other cutting-edge approaches. Importantly, many of these entrepreneurs cut their teeth in the state-run space institutions or military research labs before venturing out. This has created a virtuous cycle: talent flows from the state to startups (and sometimes back), and ideas flow both ways. The line between public and private in China’s space industry is indeed blurry. For example, a number of “private” companies are spinoffs or joint ventures involving state agencies; others receive contracts from the government for specific projects. While this muddies definitions, it also means the upstarts have access to decades of accumulated expertise. When Space Pioneer needed a reliable engine, it could simply buy one from a state-owned aerospace academy rather than develop its own from scratch – saving time and money. This symbiosis might give Chinese firms an edge in scaling up faster. However, it can cut both ways: the heavy state influence could also constrain true commercial innovation or lead to favoritism of certain “national champion” firms over others.

In sum, China’s private space sector has quickly evolved from a curiosity to a serious technological contender. With ample funding and an expanding talent pool, these companies are rapidly mastering the art of low-cost launch and large-scale satellite deployment. They’re not yet equals to SpaceX or Blue Origin in capability – SpaceX still launches far more often, and no Chinese firm has attempted anything as large as SpaceX’s Starship – but the gap is closing yearly. As Chinese rockets grow more reliable and sophisticated, we may soon see them undercut competitors on price and availability, especially in the smaller launch segment. For the global industry, that could mean cheaper options to get to orbit, but also stiffer competition for established players in the U.S. and Europe. And that brings us to the larger geopolitical picture: what does it mean when Chinese private space companies stride onto the world stage?

Global Ripple Effects: Geopolitics and Policy Shifts

The emergence of China’s SpaceX-like firms isn’t happening in a vacuum – it carries significant geopolitical implications. Space, once the exclusive arena of superpower governments, is now a commercial playing field – and China’s rise in this field is causing both excitement and anxiety worldwide. How other nations react, and how Beijing leverages its new capabilities, could reshape international partnerships, supply chains, and even the norms of space conduct.

One immediate impact is on the global launch market. For years, if a country or company needed to launch a satellite, the options were largely: buy a ride on an American rocket (SpaceX, United Launch Alliance), a European rocket (Arianespace’s Ariane or Vega), or perhaps a Russian Proton or Soyuz. China’s state-owned Long March rockets were an option too, but due to U.S. export restrictions (ITAR), Western-built satellites were effectively barred from flying on Chinese boosters. Now, with Chinese private rockets coming online, this equation could start to shift. These new companies will be hungry for business – domestic and international – and might offer very competitive prices, subsidized indirectly by government support. We could see countries outside the traditional US/EU orbit turning to Chinese launch providers for affordable access to space. For example, a Brazilian or Malaysian satellite with all non-U.S. components could potentially launch on a LandSpace or Galactic Energy rocket at a discount price, if political conditions allow. Such moves would disrupt the global supply chain dynamics: satellite manufacturers may design payloads without U.S. parts to keep launch options open, which in turn could reduce the dominance of U.S. suppliers in the satellite technology market. In essence, a bifurcation may develop – a Western-aligned space supply chain and a Chinese-aligned one, each trying to minimize reliance on the other. This echoes trends in telecom and tech. As one analysis noted, the line between China’s “public” (state) and “private” space enterprises is blurry, and that can make other nations cautious about entrusting payloads to Chinese rockets. But for some players, low cost and rapid availability might outweigh those concerns, especially if Western launchers are backlogged or more expensive.

Another geopolitical ripple: new space partnerships and alliances. Beijing has been actively courting other countries to cooperate in space, often offering attractive deals. Under the Belt and Road Initiative’s space component – dubbed the “Space Silk Road” – China is extending satellite services and know-how to partner nations across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. For instance, through its BeiDou navigation satellite system (a rival to GPS), China provides positioning services and has built ground stations in many BRI countries. BeiDou is now fully deployed with 45 satellites in orbit, and it’s touted as the “digital glue” connecting BRI infrastructure projects around the world. Many countries have eagerly signed up for access to BeiDou, satellite imagery, or communications satellites provided by China, seeing them as faster or cheaper than Western alternatives. The rise of Chinese commercial space firms could amplify this trend: instead of China just selling satellites or data as a government-to-government service, we might see Chinese companies partnering with foreign companies or governments. Imagine a Chinese startup setting up a joint venture launch site in a friendly nation, or building a satellite network for a regional bloc. In fact, something of this sort is already underway – China recently inked a deal with Djibouti in East Africa to build its first overseas spaceport there, a project worth $1.3 billion. That launch facility, slated for completion by 2027, would be co-managed with Djibouti for 30 years. It’s no coincidence that Djibouti also hosts China’s only overseas naval base; space and terrestrial geopolitics are interwoven. A launch site on African soil could extend the reach of Chinese commercial launch services (allowing equatorial launches, for instance) and signal that China’s space footprint is becoming global. This might spur the U.S. and allies to boost their own international space collaborations to keep up.

The strategic military dimension cannot be ignored either, even though we’re talking “commercial” space. The U.S. security establishment looks at China’s space advances – whether by state agencies or nominally private firms – and sees a rising challenge to America’s long-held orbital dominance. In 2024 testimony, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson warned U.S. lawmakers that China has “made extraordinary strides especially in the last 10 years” and that “we are in a race”. He cautioned that much of China’s civilian space program (including seemingly commercial projects) can have military purposes, given China’s civil-military fusion doctrine. The rapid growth of Chinese satellite networks and launch capabilities raises concerns about counterspace weapons, surveillance, and even lunar resource claims. Nelson bluntly suggested that if China gets to the Moon and establishes a presence first, it might say “OK, this is our territory, you stay out” – effectively staking a claim. Such rhetoric shows the level of strategic mistrust brewing. While it’s unlikely any nation could legally “own” the Moon, the competition to return humans to the Moon (NASA’s Artemis versus China’s planned lunar missions) is seen as a proxy for broader technological leadership. The Pentagon, too, is investing in space resilience (satellite constellations that can survive attack, anti-satellite defense, etc.) in part because a more capable Chinese space sector means a more capable Chinese military in space.

In more concrete terms, NASA and the U.S. government have responded by doubling down on alliances and rules-setting. The Artemis Accords, a U.S.-led international agreement on peaceful lunar exploration and resource use, now has over 25 country signatories – notably excluding China and Russia. It’s an attempt to establish norms of behavior for the next phase of space exploration, implicitly creating a U.S.-aligned coalition. China, for its part, has teamed with Russia to propose a rival framework (the International Lunar Research Station), and is recruiting partners for its planned Moon base in the 2030s. We are seeing a gentle carving up of the world into space blocs. The addition of powerful Chinese private companies to China’s side of the ledger only heightens this dynamic. Countries will feel pressure to choose sides in certain projects – for example, going with Starlink for broadband versus a Chinese satellite internet system, or choosing a launch contract with SpaceX versus one with a Chinese firm. Geopolitics could increasingly dictate which companies get which contracts; indeed, regulatory barriers already largely keep Chinese and U.S. space companies from directly doing business with each other.

“Disrupting supply chains” also comes into play at a more granular level. Space hardware often has global supply lines – a satellite might use an American processor, European solar panels, and be launched on an Indian rocket. But with geopolitical tensions, we could see more de-coupling of supply chains. The U.S. will likely maintain (or tighten) its restrictions on exporting advanced satellite parts to China, hoping to slow its progress. China in turn is investing in producing indigenous components for everything from spacecraft computers to sensors, to reduce reliance on Western tech. In the long run, this could create two parallel sets of space components. For instance, if Chinese satellite buses and electronics become good enough and cheaper, other countries might opt for those over Western models – particularly if buying American comes with strings attached or higher cost. Conversely, Western companies will avoid Chinese parts to stay clear of sanctions. It’s similar to how the world is bifurcating in telecom (with Huawei equipment versus Western 5G equipment). Space isn’t quite there yet, but the trend is visible.

One potential disruption is in rare earth minerals and materials for space – China dominates the production of rare earths used in electronics, and if relations worsen, one could imagine scenarios where access to those for satellite manufacturing becomes a strategic issue. Also, consider launch supply chains: SpaceX currently uses suppliers globally (though many in the U.S.), while Chinese rockets use mostly domestic suppliers. If Chinese launchers start taking global market share, some suppliers might shift focus to them. European rocket makers (like Arianespace) are already under huge competitive pressure from SpaceX; the last thing they want is a flood of low-cost Chinese launch vehicles further squeezing them. This might push Europe to consolidate and innovate more quickly (as seen in recent EU discussions to support “New Space” startups and possibly human-rated launchers in response to U.S./China advances).

All told, the rise of China’s private space sector is injecting both cooperation opportunities and competitive stress into the global space system. On one hand, more rockets and more players could mean a thriving space economy where services get cheaper – imagine affordable high-speed internet globally from constellations, or more frequent scientific missions ridesharing on cheap launches. On the other hand, it could lead to fragmented networks and heightened rivalry, where each “side” distrusts the other’s satellites (is that satellite an Earth mapper or a spy? Is that commercial space station module also hosting military astronauts?). International governance of space is notoriously slow to evolve, and now the entrance of profit-driven actors like SpaceX and China’s startups adds a new wrinkle. Existing global rules may be tested by this new era: issues like orbital debris management, satellite interference, and resource rights on the Moon will become more pressing as more entities (state and private) jostle for position. There’s a growing recognition that dialogues between the U.S., China, and others are needed to prevent misunderstandings – but so far, political barriers (like America’s ban on NASA-China cooperation) make such discussions difficult.

What Should the U.S. Do? – Strategy in an Era of New Space Competitors

China’s surging private space sector presents the United States with both a challenge and an impetus to get its own house in order. For years, American space leadership – bolstered by innovative companies – has been taken somewhat for granted. SpaceX launches dominate the commercial market, NASA’s science missions lead in discoveries, and the U.S. military operates the most advanced satellites. But complacency now would be a mistake. As China Inc. reaches for the cosmos, the U.S. must respond with confidence, creativity, and a clear strategy to retain its edge. Here are a few key moves and considerations:

1. Double Down on Innovation and Investment: The best way to meet a competitive challenge is through excellence, not exclusion. The U.S. should continue (and expand) support for homegrown innovation in space technology. This means funding R&D in next-generation propulsion, lunar mining, space nuclear power, and other breakthrough tech that could leapfrog current capabilities. NASA’s partnerships with private companies – exemplified by the Commercial Crew and Artemis programs – should serve as a model. For instance, NASA is already contracting firms like SpaceX to develop the Starship human lander for the Moon, and investing in startups for lunar surface systems. These collaborations blend NASA’s expertise with commercial agility, and they should be broadened. More prizes, seed grants, and public-private partnerships can ensure the U.S. stays on the cutting edge. SpaceX shouldn’t be the only success story – encouraging a diverse ecosystem (from giants like SpaceX and Blue Origin to niche startups in robotics or habitats) will keep America ahead of the curve. Remember, China’s whole strategy is to emulate the success of Silicon Valley in space; the U.S. must continue to be the place where the boldest space ideas are born and realized.

2. Shore Up Alliances and Global Presence: One clear advantage the U.S. has is a wide network of allies and partners in space. America should intensify cooperative projects with Europe, Japan, Canada, India, and others to pool talent and resources. The Artemis Accords and the multinational Artemis program to return to the Moon are great examples – with Europe providing service modules, Canada building robotic arms, Japan working on components, etc. By sharing the journey (and costs), the U.S. and its allies can accomplish more than China’s relatively go-it-alone approach. It also gives neutral countries an attractive coalition to join, counterbalancing China’s offerings. The U.S. might consider expanding satellite-sharing agreements (for Earth observation, disaster monitoring, GPS access) to countries that might otherwise be drawn to China’s services. Basically, make sure that friendly nations see partnership with the U.S. as the more beneficial path for their own space aspirations. Diplomatic engagement in forums like the UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space is also key – to promote norms on things like debris mitigation, satellite coordination, and not conducting destructive ASAT tests (a promise the U.S. has made and is urging others to adopt). If the U.S. leads in setting fair rules, it can gently pressure China to either join or risk isolation in global rule-making.

3. Guard the Technological High Ground (but pick battles wisely): U.S. export controls (like ITAR) have long restricted space tech transfer to China, and that’s unlikely to change given strategic concerns. It’s reasonable to protect truly critical security technologies. However, the U.S. might reevaluate certain commercial export policies to avoid unnecessarily driving allies or customers into China’s arms. For example, if American satellite manufacturers can’t sell to certain countries, those countries will simply buy from China. In some cases, a bit more flexibility for U.S. companies (with proper vetting) could keep them competitive globally and stave off Chinese encroachment. Moreover, the U.S. should invest in its own industrial base for things like microelectronics, materials, and rocket components, so it isn’t dependent on imports that could be cut off in a crisis. The Biden administration’s recent moves to bolster domestic semiconductor and battery production have parallels in space – ensuring the U.S. can produce what it needs for satellites and rockets without foreign chokepoints. Essentially, stay ahead in the “space supply chain” game: if China builds a space station, we build a bigger one with our partners; if they pour money into reusable rockets, we perfect fully reusable and super heavy-lift rockets (like SpaceX’s Starship, which aims to vastly out-lift anything China has for now). Technological high ground also means things like quantum satellites, AI-driven space traffic management, and even exploration of Mars and beyond – areas where U.S. research leadership can pay off in both prestige and strategic advantage.

4. Address the New Threats: With more Chinese satellites and rockets in orbit, the U.S. military and intelligence community need to ensure they can protect American and allied space assets. That’s a core reason the U.S. Space Force was created in 2019. Continued development of technologies to rapidly replace satellites (like small sat swarms), harden them against jamming or cyberattacks, and track objects in space (to attribute any hostile actions) is critical. While this veers away from the “commercial” realm, it’s the backdrop against which all these private activities occur. If Chinese companies begin launching hundreds of satellites, some of those could have dual-use capabilities that worry defense planners. The U.S. should extend its current policy of not purchasing Chinese space services (for example, NASA and Pentagon won’t be buying Chinese launch rides) and also help allies secure their systems. On the flip side, the U.S. must be careful not to overreact and paint every Chinese satellite launch as a threat – there is a balance to be struck between vigilance and paranoia. Confidence-building measures (like communication channels to avoid satellite collisions or interference) with China could actually reduce risk.

5. Don’t Shut the Door on Cooperation: This one is tricky, but worth pondering. Even at the height of the 1960s space race, the U.S. and Soviet Union found moments to cooperate (the Apollo-Soyuz handshake in 1975, for example). With China, meaningful civil space cooperation has been largely off-limits due to U.S. policy (the Wolf Amendment) and China’s military-linked program. However, the international community as a whole would benefit from some basic cooperation – sharing data on space debris, coordinating planetary defense against asteroids, perhaps joint efforts on scientific probes. These are areas where politics could be put aside for mutual gain. If Chinese private companies truly become more independent and globally engaged, they might participate in international collaborations (say, a radio telescope network on the Moon involving many countries’ contributions, including Chinese hardware). The U.S. should remain open to pragmatic, carefully structured cooperation that serves the interests of global safety or science. That doesn’t mean embracing China’s space program with open arms – the mistrust runs deep for valid reasons – but it does mean not slamming the door completely. Sometimes engagement can also be a form of influence.

At the end of the day, the rise of China’s private space sector should be a Sputnik-like wake-up call – not for an arms race, but for a race of innovation and policy agility. The U.S. retains huge advantages: a richer experience with commercial space, more proven companies, and an open society that attracts top talent from around the world (including China – many U.S. space scientists and tech entrepreneurs are Chinese-American or were trained in the States). America should play to those strengths. It should ensure that its immigration and education policies continue to welcome and produce world-class engineers and scientists who will drive the next wave of breakthroughs. It should also strive to demonstrate the value of its model: when private enterprise and public institutions collaborate in the U.S., we got reusable rockets and Mars rovers; when they collaborate in China, we’re now seeing similar achievements. Showing that the democratic, open-market approach can outperform in the long run is perhaps the most powerful response.

Finally, the U.S. and its allies should approach this new era not with fear, but with a sense of opportunity and responsibility. A little healthy competition can spur incredible progress – we may be entering a golden age of space development where humans return to the Moon, set foot on Mars, and build ventures in orbit that we can’t yet imagine. China’s growing participation in this arena, private sector included, means more minds tackling the big challenges of space. The U.S. will of course act to protect its interests, but it should also recognize that space is vast and potentially accommodating of many players. There is room for cooperation even amid competition. Crafting a strategy that balances these forces will be tricky, but it’s necessary to avoid conflict and ensure space remains a domain of peaceful exploration and commerce.

In conclusion, China’s private space surge marks a pivotal moment for the global space industry. It’s significant not just for what it says about China’s technological rise, but for what it means to everyone else with cosmic ambitions. American policymakers would do well to watch developments in Shenzhen and Beijing as closely as those in Hawthorne and Houston. The race is on – not the old Cold War race of ideologies, but a 21st-century race of innovation ecosystems. And as history has shown, in races like this the winners will be those who stay adaptive, collaborative, and focused on the future. The rockets taking off from China’s Gobi Desert are a clear sign: the new space age just got a lot more interesting. Keeping it peaceful, prosperous, and beneficial to all will require the best from both East and West. The sky, quite literally, is no longer the limit.