ESA’s record budget and new “European Resilience from Space” programme mark a quiet but profound shift in how Europe thinks about space, security and industrial power.

On 26–27 November 2025, European ministers meeting in Bremen approved the largest budget in the European Space Agency’s 50-year history: €22.1bn for the next three years, up from €16.9bn in the 2023–25 period. For once, member states almost fully matched what ESA had asked for – something insiders cannot remember happening before.

Money alone would be newsworthy. But what makes this ministerial different is where some of that money is going. For the first time, ESA will run a programme whose mandate explicitly includes non-aggressive defence: European Resilience from Space (ERS), a dual-use constellation designed to stitch together Europe’s national satellites into something closer to an intelligence-grade network.

Europe is not abandoning science. The new package also boosts funding for exploration, climate monitoring and commercialisation. Yet taken together, the record budget, the ERS programme, and a wider EU push around secure connectivity and space regulation amount to a space reset: a shift from treating space as a mainly peaceful, technocratic domain to seeing it as a strategic infrastructure that must serve defence and economic security as much as science.

Table of Contents

ToggleA budget that finally matches the rhetoric

ESA’s new three-year envelope of €22.1bn represents roughly a 30% nominal increase over the previous €16.9bn package. On an annualised basis, that works out at about €7.4bn per year, still far below NASA’s FY2024 budget of $27.2bn but a meaningful step-up in European terms.

The headline figures conceal important choices. Ministers agreed to spend €4.4bn on space transportation, about 20% more than in the previous cycle, and €3.5bn on Earth observation, a 16% rise. A further €3.6bn has been earmarked for co-funded programmes designed to crowd in private investment – from satellite hardware to downstream data platforms – with ESA explicitly promising to “boost innovation and strengthen SMEs and new entrants”.

Even after this boost, Europe remains a mid-sized space power in budgetary terms. The global space economy reached $613bn in 2024, according to the Space Foundation, while global public space budgets totalled about €120–135bn, depending on methodology. An EU policy paper put Europe’s public civil and military space spending at €12.6bn in 2024, or roughly 10% of global government outlays – despite the continent accounting for a far larger share of world GDP.

Consultants at Roland Berger estimate that, on current trends, Europe’s share of the global space market could slide from 17% in 2024 to about 12% by 2040, even as the market itself doubles or triples in size. Against that backdrop, the Bremen decisions look less like exuberant spending and more like a defensive investment: a way to slow relative decline in a sector that is increasingly entangled with national power.

From “peaceful uses” to dual-use by design

For decades, European space policy – both at ESA and in the EU institutions – was framed in resolutely civilian terms. Flagship programmes such as Galileo (navigation) and Copernicus (Earth observation) were justified on grounds of economic spillovers, environmental monitoring and “peaceful uses” of outer space.

In practice, these systems were always dual-use. Precision navigation and high-quality imagery are as useful for militaries as they are for farmers or logistics firms. But the security dimension was largely implicit, and legal and technical limits – for example on image resolution and revisit rates from Copernicus satellites – constrained how far EU assets could support defence planners.

That posture has shifted sharply in the last three years. The EU’s 2022 Strategic Compass formally designated space as a “strategic domain”, while the 2023 EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence argued that Europe must treat space services, from navigation to communications, as critical enablers of military operations and crisis response. Analysts describe this as a paradigm change: for the first time the EU is openly pursuing what one think-tank calls “hard-power capabilities in the space field”, backed by new pilot programmes for space domain awareness and a governmental Earth-observation service.

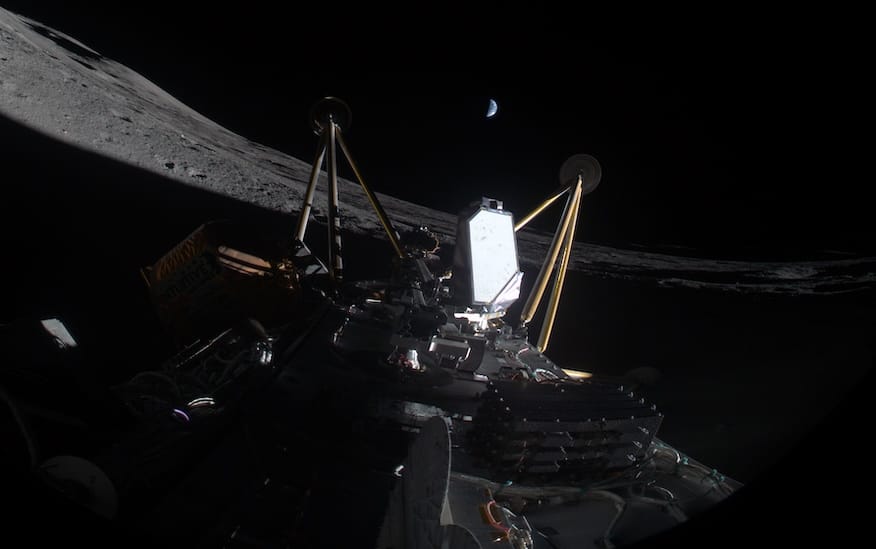

The war in Ukraine accelerated that turn. European briefings are blunt about the lesson from Kyiv: commercial constellations and foreign-owned systems – from Starlink to US optical satellites – have been vital to Ukraine’s defence, but they also underscore Europe’s strategic dependence on non-European infrastructure. ERS and related programmes are, in effect, an attempt to ensure that the next conflict in Europe’s neighbourhood is supported by European-controlled “eyes and ears” in orbit, even if allied systems remain indispensable.

European Resilience from Space: a new nervous system

ERS sits at the heart of ESA’s new security posture. Ministers approved around €1.2bn for the programme out of a requested €1.35bn, making it about 5% of the total ESA package – modest in cash terms but symbolically significant.

ESA describes ERS as a dual-use Earth-observation and services network rather than a classic “spy satellite” programme. The idea is to pool and share high-resolution imagery and data from existing national and European satellites, then plug gaps with new assets, while adding services such as secure connectivity, low-Earth-orbit navigation and spectrum monitoring.

The programme is also designed as the first building block for the EU’s planned Earth Observation Governmental Service (EOGS) – a future EU-run system intended to give member states highly reactive, independent imagery for everything from border surveillance to disaster response. ERS thus acts as a bridge between ESA’s technical expertise and the EU’s growing appetite to wield space assets as part of its wider security and defence strategy.

There is a political novelty as well. ESA’s own communication on CM25 notes that ministers have now given the agency a “clear mandate” to use space applications for non-aggressive defence purposes, while leaving subscriptions to ERS open for another year to allow hesitant capitals to join later. For an organisation that has historically kept defence at arm’s length, that is a considerable cultural shift.

IRIS²: the other half of the dual-use story

ERS is only one part of Europe’s security-space puzzle. On the communications side, the European Commission is pressing ahead with IRIS², a €10bn-plus secure connectivity constellation that will deploy around 290 satellites in low and medium Earth orbit.

IRIS² is the EU’s third flagship space project after Galileo and Copernicus. It is explicitly framed as an answer to commercial mega-constellations such as Starlink – designed to provide encrypted government communications, support military and crisis-management operations, and extend broadband coverage to remote regions, all under European regulatory and political control.

The system will be rolled out in stages. Existing national satellites will be pooled under the EU’s GOVSATCOM framework from 2025, with full IRIS² governmental services expected by 2030 once EU-owned infrastructure is in place. A consortium of incumbents and “new space” operators will finance, build and operate the constellation under a concession model, with ESA acting as technical partner and the EU Space Programme Agency (EUSPA) overseeing services.

Where ERS gives Europe sharper “eyes” on Earth, IRIS² is about “nerves and voice” – a sovereign communications backbone for a continent that is increasingly worried about being cut off from foreign-owned networks in a crisis.

Industrial policy in a security wrapper

Look closely at the Bremen numbers and another logic emerges: industrial policy. ESA and the Commission are using security language to underpin investments that are just as much about jobs, technology and competitiveness.

The €4.4bn for space transportation will finance upgrades to Ariane 6 and Vega-C, modernise launch infrastructure and significantly expand the European Launcher Challenge, a competitive scheme aimed at nurturing a new generation of small and medium launch providers. The Launcher Challenge alone has now attracted about €900m in subscriptions and shortlisted five private companies, from Germany’s Isar Aerospace to Spain’s PLD Space, to compete for institutional launch contracts.

On the applications side, ESA’s €3.6bn commercialisation budget is intended to crowd in “substantial private funding” by co-funding hardware, data platforms and services, building on the network of ESA Business Incubation Centres across Europe. In effect, European taxpayers are being asked to underwrite the early stages of an ecosystem that can compete with US and Chinese space companies, especially in Earth observation analytics, in-orbit services and security-related applications.

This sits alongside the Commission’s proposed EU Space Act, unveiled in June, which aims to create a single internal market for space services, with common rules for debris mitigation, cybersecurity, safe disposal of satellites and environmental impact. For European operators, that combination of demand (through ERS and IRIS²), supply-side support (through ESA programmes), and a unified regulatory framework is meant to lower barriers to entry and give scale to firms that often struggle to find anchor customers.

Who pays, who leads – and who feels left out

Budgets also tell a story about power. Germany has emerged as ESA’s largest single contributor, lifting its three-year commitment from just under €3.5bn three years ago to more than €5bn, roughly 23% of the total. Berlin’s pledge sits within a national space security strategy that foresees up to €35bn in space-related defence investment over the coming years.

France, long the traditional leader of European space efforts, remains a heavyweight but is constrained by a domestic budget squeeze. Commentary in the French press has already cast CM25 as a moment when Germany and Italy gain clout at France’s expense, with the UK – now outside the EU but still an ESA member – losing influence as it trims subscriptions and withdraws from missions such as the TRUTHS climate satellite.

For smaller states, the picture is more mixed. Ireland, for example, used the Bremen meeting to trumpet a €170m commitment as a way to buy access to a technology ecosystem “with a value of over €5bn per year, that has no equal anywhere outside NASA”. Some Central and Eastern European members are raising their stakes too, seeing space as a way to move up the value chain without the heavy industrial baggage of older member states.

Yet the politics of “geographical return” – ESA’s rule that member states receive industrial contracts roughly in line with what they pay in – still exerts a gravitational pull. It helps lock in political support, but critics argue that it fragments programmes and slows decision-making, especially in fast-moving areas like launch and newspace services. ERS and IRIS² will test whether security-driven projects can overcome those structural frictions.

Europe’s awkward governance triangle

Behind the budget lines lies a more subtle challenge: governance. Europe’s space apparatus is spread across at least three overlapping centres of gravity:

- ESA, an intergovernmental agency with 23 member states (including non-EU countries such as the UK, Norway and Switzerland), historically focused on civil science and technology;

- The European Union, which funds and regulates major programmes like Galileo, Copernicus and now IRIS², and which is building its own security-driven agenda;

- National defence establishments, which own and operate much of Europe’s truly sensitive space hardware and retain ultimate responsibility for military operations.

Recent EU documents talk openly about a “hybridisation” of EU space policy and defence policy, with civil assets increasingly used for security purposes and, conversely, defence goals shaping the evolution of civil programmes. The EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence calls for more systematic cross-fertilisation, dual-use technology development and shared threat assessments – including an annual classified review of the space threat landscape.

ERS crystallises this triangle. The programme is run by ESA, but explicitly designed to feed into an EU-branded governmental service and, ultimately, into national defence planning. That raises sensitive questions: Who decides which users see what data, and when? How are national caveats handled? What happens if defence needs collide with civilian privacy or commercial competition rules? Those questions are largely left for later – but the decisions taken in Bremen mean they can no longer be dodged.

A contested orbit, a crowded balance sheet

Europe is not pivoting to security in a vacuum. Global government space investment reached about $135bn in 2024, with defence now accounting for more than half of that – a structural break with the historically civil-dominated pattern.

Russia, China, the US and a growing cast of regional powers are deploying anti-satellite weapons, electronic warfare capabilities and purpose-built military constellations. Western analyses now routinely treat space as a contested domain, not just for satellites but for cyber-attacks on ground infrastructure and data links.

At the same time, space is simply getting crowded. The EU Space Act proposal notes around 128 million pieces of debris already in orbit, with thousands more satellites planned, and moves to impose mandatory end-of-life disposal, collision-risk assessments and cybersecurity obligations on operators that want to serve the EU market.

For European finance ministries wrestling with tight budgets and ageing populations, these trends create an uncomfortable equation: rising strategic risk + growing commercial opportunity + finite fiscal room. The Bremen package is, in part, an attempt to square that triangle by leveraging public money to unlock private capital, while using security and resilience as the political narrative that justifies higher spending.

What to watch over the next three years

Whether this space reset sticks will depend less on this week’s headlines and more on what happens between now and the next ESA ministerial.

Several milestones will be telling:

- ERS procurement and governance. How quickly ESA can move from concept to operational capability – and how transparent the rules become around tasking, data access and the interface with national militaries.

- IRIS² execution risk. The concession model depends on a fragile equilibrium between incumbent primes and newer operators. Delays or cost overruns could revive doubts about Europe’s ability to deliver large constellations on time.

- The European Launcher Challenge. A handful of small-launcher firms now have a real shot at institutional contracts. Their success or failure will say much about whether Europe can sustain a competitive launch ecosystem alongside Ariane 6 and Vega-C.

- EU Space Act negotiations. Member states will have to agree how strict to be on debris rules, cybersecurity and environmental standards – and how far to apply them to non-EU operators. The balance they strike will influence Europe’s attractiveness as a market and regulatory model.

- Integration with NATO and national defence strategies. As NATO updates its own space posture, European capitals will need to reconcile ESA/EU initiatives with alliance plans, ensuring that investments in ERS and IRIS² genuinely complement, rather than duplicate, allied capabilities.

For now, Bremen marks a notable moment. Europe has decided that space is no longer just about exploration and climate science. It is about strategic autonomy, digital sovereignty and resilience – and about whether Europe wants to be a rule-taker or a rule-maker in an increasingly crowded orbit.

The numbers agreed this week will not, on their own, close the gap with the US or China. But they do signal that Europe is finally prepared to put substantial money, and a degree of political courage, behind a more hard-headed view of what space is for.