Not so long ago, “cloud regions” were just dots on terrestrial maps: clusters of servers parked next to cheap electricity, cold air and willing regulators.

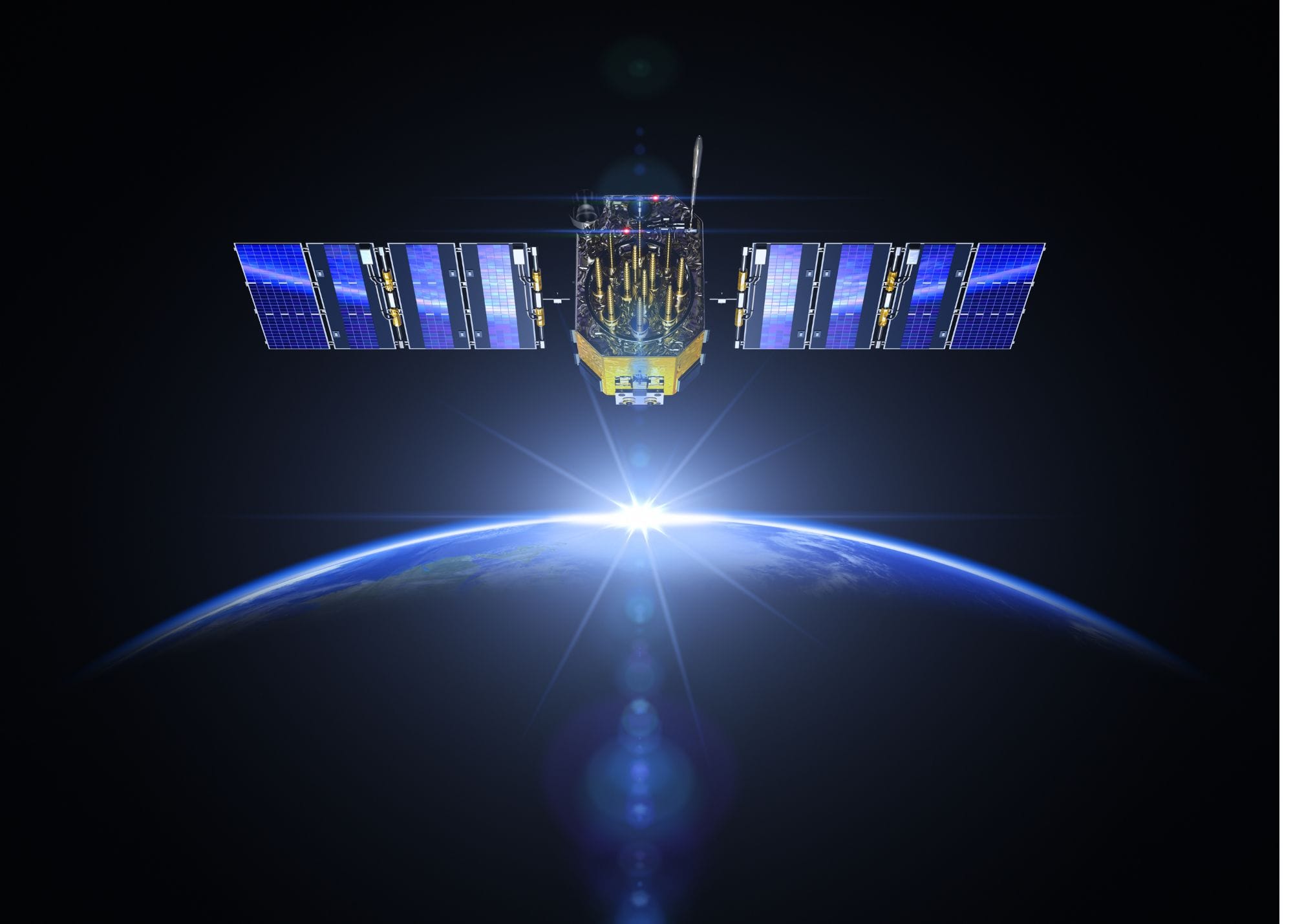

Now, a new set of dots is being sketched—this time in orbit.

In the past few weeks, a handful of announcements have moved “space-based data centres” from science-fiction slide decks into the early stages of an industry. US startup Aetherflux has unveiled Galactic Brain, a plan to deploy solar-powered AI data-centre satellites from 2027 onwards. Blue Origin has been quietly working on orbital AI data-centre technology for more than a year, according to reports, with Jeff Bezos arguing that gigawatt-scale data centres will migrate to space within 10–20 years. SpaceX, for its part, has floated the idea of turning future Starlink satellites into an AI computing mesh.

They are not alone. Axiom Space is preparing “orbital data centre” nodes for its commercial station. In Europe, Thales Alenia Space has led an EU-funded study, ASCEND, on gigawatt-class space data centres for the bloc’s climate and digital-sovereignty goals. Others—from Nvidia-backed Starcloud, which talks about a 5 GW orbital complex, to regional players like Madari Space in Abu Dhabi—are racing to claim a slice of what some are already calling “galactic cloud regions”.

Behind the branding is a simple question: is shifting AI compute into orbit a serious answer to Earth’s energy crunch—or just a very expensive detour?

Table of Contents

ToggleThe AI power crunch behind the orbital pitch

The underlying driver is not fashion; it is electricity.

According to the International Energy Agency, data centres consumed around 415 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity in 2024—roughly 1.5% of global demand—and that figure has been growing by about 12% a year. By 2030, the IEA expects global data-centre consumption to more than double to about 945 TWh, slightly more than Japan uses in a year.

Artificial intelligence is the main accelerant. Goldman Sachs now estimates that overall data-centre power use could jump 175% from 2023 levels by 2030, with AI workloads taking a much larger share of that total. In some scenarios, AI could account for 35–50% of data-centre electricity consumption by the end of the decade.

In the United States, the Department of Energy reckons data centres already consume about 4.4% of the country’s electricity. On current trajectories, that could rise to between 6.7% and 12% by 2028. BloombergNEF projects that US data-centre power demand will more than double by 2035, with average hourly load almost trebling. Similar pressures are visible in Europe and parts of Asia.

The pinch is not just electricity. Data-centre cooling is increasingly a water story. Large facilities can use up to 5 million gallons a day—the equivalent of a town of tens of thousands of people. In 2023, Meta’s data centres alone consumed about 776 million gallons of water, roughly 95% of its global usage, while Google has had to defend water-intensive sites in places like The Dalles, Oregon.

Those numbers are colliding with politics. Locals have pushed back against hyperscale sites that draw heavily on power grids and aquifers. Grid operators warn of bottlenecks. Coal and gas plants are being re-examined as potential “AI peakers”. The UK’s Drax Group, for instance, now plans to convert part of its North Yorkshire power plant into a 100-megawatt data centre—scaling to over a gigawatt after 2031—to feed AI demand directly from the grid.

In that context, the pitch for space sounds almost disarmingly neat:

- No land: no planning fights over suburban server farms.

- No water: radiate heat into the vacuum instead of boiling rivers.

- 24/7 sunlight: park in orbits with near-constant solar exposure and tap effectively unlimited power.

If AI is becoming a race for compute—and compute is a race for clean, continuous energy—it is not hard to see why entrepreneurs and investors are looking upwards.

What space actually offers

As a physical environment, low Earth orbit (LEO) and beyond are undeniably attractive for certain aspects of computing infrastructure.

First, energy. In high-inclination orbits chosen to maximise exposure, satellites can bask in near-constant sunlight. The IEA notes that one of the main constraints for data centres on the ground is the speed at which new electricity infrastructure can be built; in space, the limiting factor is launch capacity and solar hardware, not permits and pylons.

Bezos has popularised a vision of gigawatt-scale solar power stations driving data centres in orbit, predicting that such facilities could eventually outperform terrestrial ones within 10–20 years. The European ASCEND study, led by Thales Alenia Space for the European Commission, has explored constellations of satellites with a combined 10 MW of computing capacity as a first step—comparable to a medium-sized data centre today, and a fraction of the gigawatt scale advocates ultimately imagine.

Second, cooling. At the edge of space, radiators can dump heat directly into the cold background of the universe. That does not mean cooling is “free”—large radiating surfaces still need to be launched, deployed and kept pointed correctly—but it removes water from the equation and reduces dependence on ambient air or chilled liquids.

Third, isolation. Space is far from immune to cyber attack, but an orbital data centre is physically separated from terrestrial threats and grid disturbances. Backers such as Axiom Space argue that in-orbit cloud services, linked via optical inter-satellite links, will offer resilient storage and compute for national-security customers and sovereign agencies.

Finally, there is a latency twist. For certain use cases—such as routing traffic between continents—an orbital relay can reduce total distance travelled through fibre, potentially cutting lag. Some advocates argue that placing compute closer to Earth-observation satellites could also reduce bottlenecks by processing data in space rather than downlinking raw feeds.

None of this automatically adds up to the sort of “galactic cloud region” that can train trillion-parameter models. But it does explain why a diverse cast of players is suddenly paying attention.

The new orbital data-centre players

The emerging landscape breaks roughly into three camps.

1. Power-first players

Aetherflux is perhaps the most emblematic of the new entrants. Founded in 2024 and backed with about $60 million to demonstrate space-based solar power, the company initially focused on beaming energy to Earth via infrared laser. This year it widened its ambition with Galactic Brain, a constellation that would both perform AI compute in orbit and deliver power to “contested environments” on the ground.

In public statements, Aetherflux’s founder Baiju Bhatt—better known as the co-founder of Robinhood—frames the race for artificial general intelligence as fundamentally a race for compute, and hence for energy. The firm argues that Earth-based infrastructure cannot be built quickly enough and that bypassing terrestrial constraints is essential. Its first data-centre satellite is pencilled in for 2027, with a separate demonstration of power-beaming hardware planned earlier.

Starcloud, another high-profile entrant, has laid out plans for an orbital data centre with up to 5 GW of computing power, using super-sized solar and cooling panels roughly four kilometres wide. On paper at least, that would rival the output of large terrestrial power plants.

2. Cloud-and-station operators

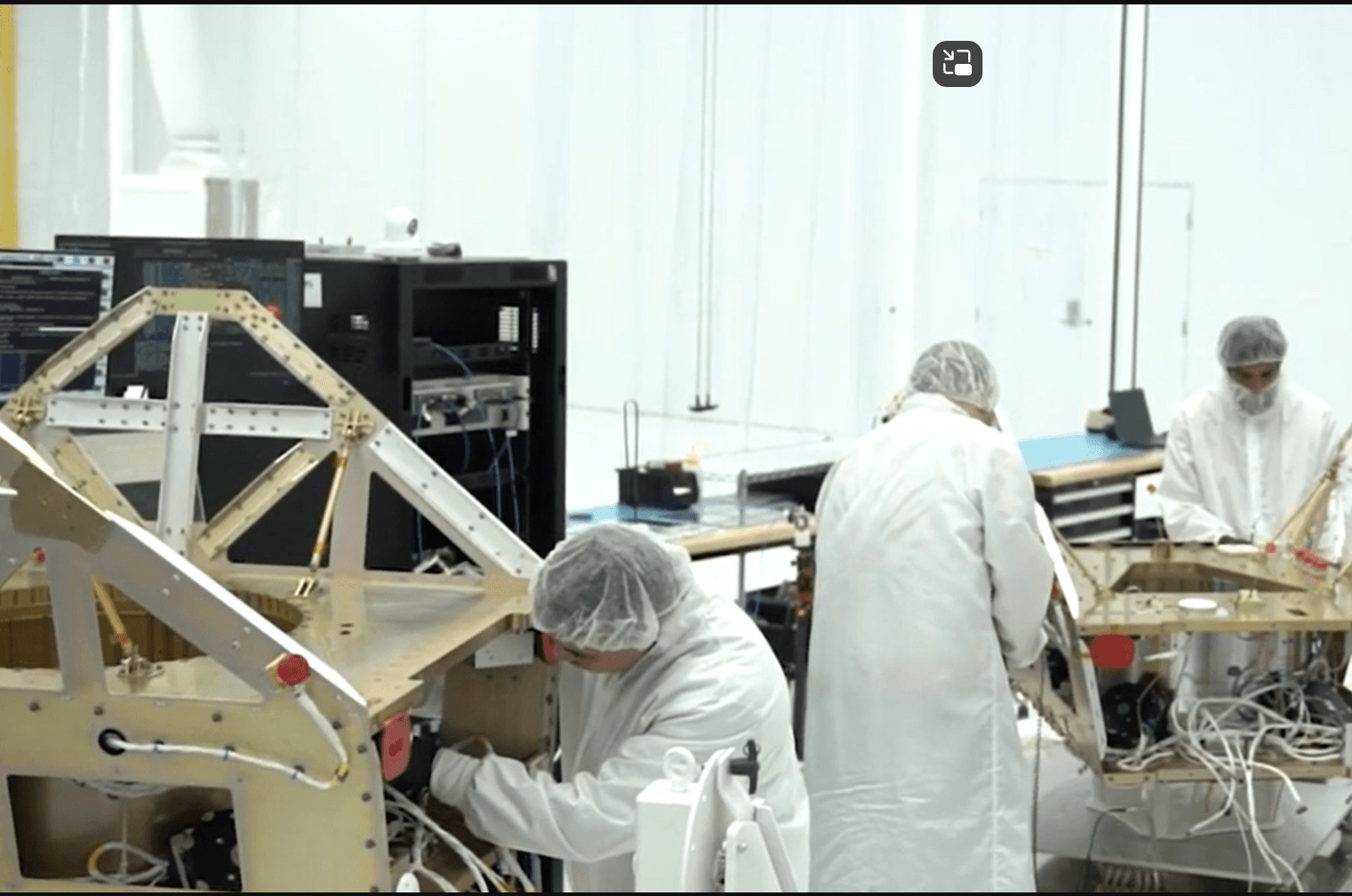

Axiom Space sits in a different category. It is already building a commercial space station, partly funded through NASA contracts, and has announced that it will launch its first two orbital data-centre nodes to LEO by the end of 2025. These “ODC T1” nodes are pitched as secure, laser-linked storage and compute for national-security and commercial clients—more an extension of cloud regions into orbit than a wholesale move of compute away from Earth.

Other station projects are watching. Axiom’s main rivals—Starlab (Voyager/Airbus), Orbital Reef (Blue Origin/Sierra), and Chinese state-backed stations—have yet to set out equally detailed orbital cloud strategies, but most assume that in-station data services will be part of their eventual revenue stacks.

3. Demonstrators and regional players

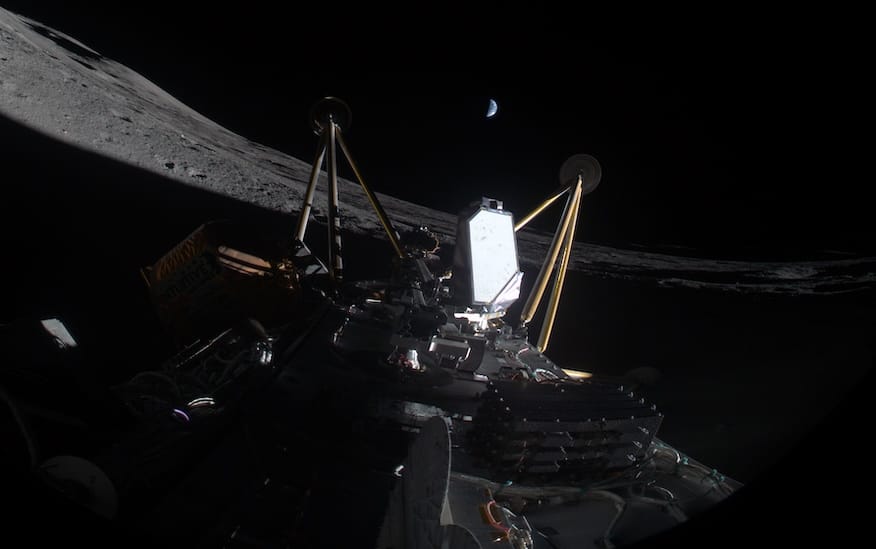

Further down the stack are companies using smaller payloads to probe elements of the idea. Lonestar Data Holdings has already operated a tiny data centre on the Moon as a backup and restore service—its “Freedom Data Center” survived even after the lander carrying it tipped over, in what the firm likened to a “Kitty Hawk moment” for space computing.

Madari Space in Abu Dhabi plans to send toaster-sized data-centre components into orbit to test on-board processing and networking concepts, while European research groups have modelled communications architectures for space-based data-centre clusters across LEO, MEO and GEO.

Add to that a loose constellation of cloud providers, chipmakers and defence contractors quietly exploring orbital compute—and the outlines of a genuine ecosystem emerge.

The physics problem: mass, heat and distance

The sheer enthusiasm can obscure some stubborn physics.

Mass and launch. Building a gigawatt-scale solar array in orbit is not just a matter of buying panels. Analysts estimate that a 1 GW space solar plant could require several million square metres of photovoltaic surface, plus radiators, structures and the computing hardware itself. At today’s launch costs, simply lofting the solar hardware for such a system could run into tens of billions of dollars; one estimate puts the bill for solar equipment alone at over $25 billion, before counting radiators or servers.

SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn are designed precisely to slash those costs by increasing payload and reusability. But even under optimistic scenarios, building the equivalent of a hyperscale campus in orbit is closer to constructing an offshore oil platform than spinning up a warehouse.

Thermal management. While space is “cold”, it does not conduct heat away. Data-centre hardware would sit inside a controlled environment that must get rid of waste heat via radiative panels. The more compact and power-dense the GPUs, the harder it is to keep them within safe operating temperatures. Designs like Starcloud’s envision kilometre-scale radiator wings.

Radiation and reliability. On the ground, data-centre operators worry about power quality and cooling failures. In space, cosmic rays and trapped charged particles add an extra source of bit-flips and hardware degradation. Radiation-hardened chips are far more expensive and less performant than mainstream GPUs; shielding adds yet more mass. Some proponents suggest using relatively standard accelerators and accepting higher error rates, compensated for in software. That remains unproven at exascale.

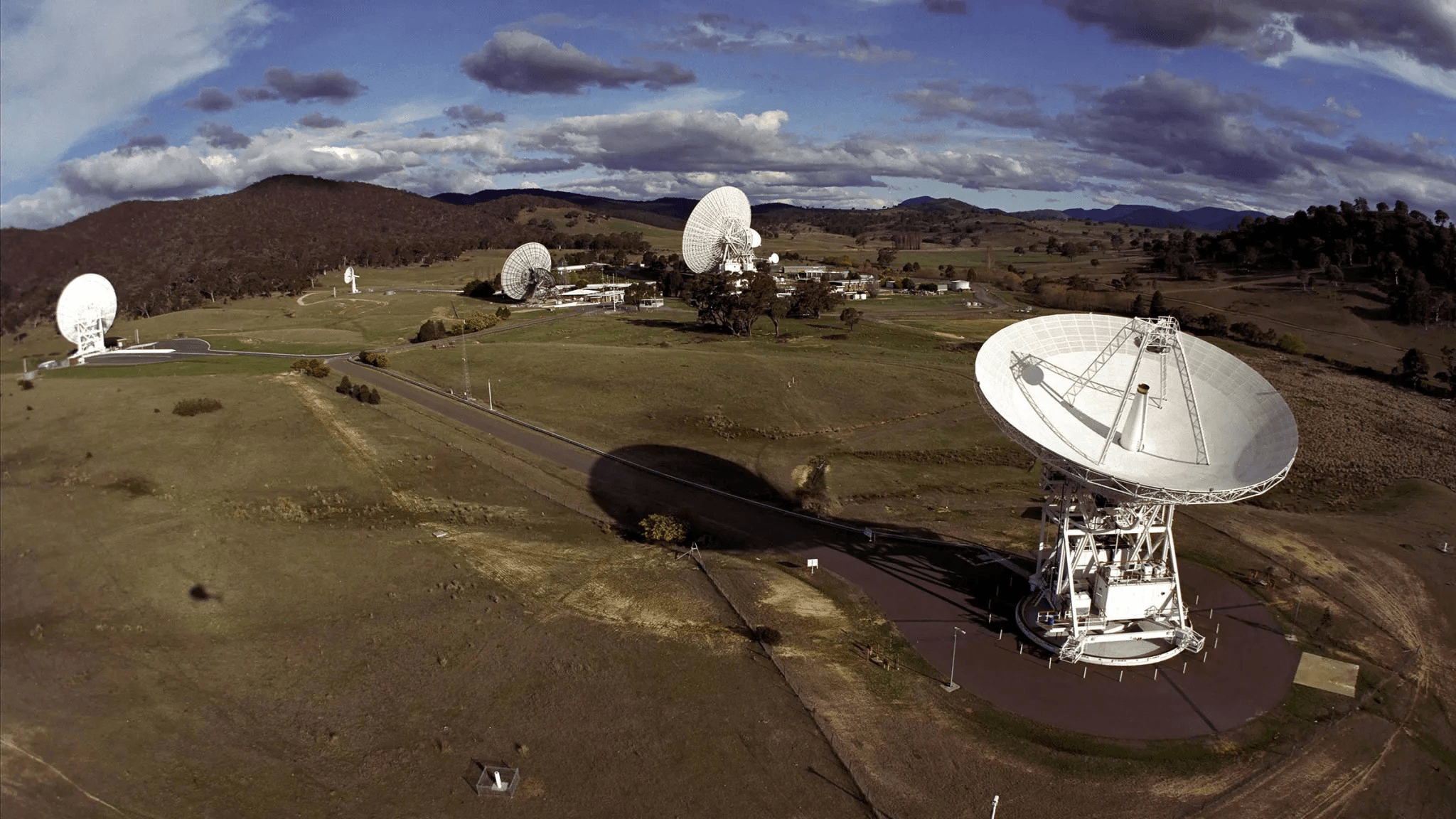

Latency and bandwidth. For AI training, raw throughput matters more than shaving a few milliseconds. Moving petabytes of training data from Earth to orbit, and results back again, will require vast optical links and ground stations. Some concepts sidestep this by focusing on workloads that originate in space—Earth-observation processing, in-orbit sensor fusion, national-security tasks—but those are niche compared with generic cloud AI demand.

Even for intercontinental routing, gains are not automatic: a mis-placed orbital relay could add hops rather than reduce them. Designing true “galactic routes” will require careful integration with terrestrial fibre.

For all those reasons, many in the conventional data-centre industry view orbital projects as interesting edge cases rather than core infrastructure—at least for now.

The economics: who pays for a galactic region?

If the engineering barriers are formidable, the business case is more so.

Traditional cloud economics rely on scale and standardisation. Hyperscalers amortise the cost of land, construction and grid connections over millions of tenants, using off-the-shelf hardware and automation to squeeze out marginal gains.

Orbital data centres, by contrast, begin with bespoke hardware, bespoke launch and bespoke operations. Insurance costs are high: underwriters are still grappling with how to price collision, debris and cyber risks in LEO, especially for large, powered structures.

Advocates counter that their costs should be compared not to average data centres, but to the marginal cost of the next wave of AI capacity. Here, the numbers are more fluid. New terrestrial projects increasingly require expensive grid upgrades and long-distance transmission lines. Local opposition can delay multi-billion-dollar campuses for years. Goldman Sachs and others now warn that power scarcity may be a binding constraint on AI growth in specific regions.

In that light, an orbital array that taps abundant sunlight and avoids water and land fights might look less outlandish—especially if paired with lucrative defence or sovereign-cloud contracts.

A second economic plank is carbon policy. The EU’s interest in ASCEND is explicitly tied to climate goals: the project envisions space-based data centres supporting Europe’s Green Deal by shifting some of the most power-hungry workloads off-planet, powered entirely by solar. Whether such a shift would truly count as an emissions reduction—given launch, manufacturing and end-of-life impacts—remains a subject of debate among environmental economists.

The most realistic early path may be hybrid: modest orbital nodes providing specialist services (for example, secure processing for classified imagery or in-space manufacturing telemetry), priced at a premium, rather than wholesale displacement of cloud regions on the ground.

Regulation, sovereignty and the politics of galactic cloud

If building a data centre in space is hard, regulating one will be harder still.

Today’s cloud regions are neatly tied to jurisdictions. Companies choose “US-West” or “EU-Central” not just for latency, but for compliance with national data laws. In orbit, the situation blurs. Ownership follows the launching state under the Outer Space Treaty, but data could be processed above multiple countries without ever touching their territory.

Governments are unlikely to leave that ambiguity unchallenged. European regulators are already exploring how to extend cyber-security and data-protection rules to space-based infrastructure, building on threat-landscape work from agencies such as ENISA. NATO and national defence ministries, meanwhile, are folding space cyber scenarios into war-gaming.

Commercial operators will also have to navigate export-control regimes. Data centres packed with advanced AI accelerators are, in effect, floating collections of dual-use technology. Controls similar to those now applied to chip exports to certain countries could easily extend to orbital capacity leasing.

Sovereignty cuts both ways. For some states, a “galactic region” hosted by an ally’s station may be more attractive than relying on onshore foreign-owned facilities. For others, keeping critical workloads strictly within national borders will remain non-negotiable, whatever the attractions of perpetual solar power.

So, is it all hype?

It is tempting to dismiss the flurry of announcements as a familiar pattern: a hot technology (AI), a familiar bottleneck (energy), and a group of founders and billionaires offering to solve both by going to space.

There is certainly hype. Concept art often glosses over the realities of maintenance, upgrade cycles and orbital debris. Some proposals read more like marketing for broader space-industrial ambitions than near-term business plans.

But it would also be a mistake to treat the whole notion as frivolous. A few sober conclusions are emerging:

- The energy problem is real and structural. Multiple independent analyses—by the IEA, national energy departments, banks and consultancies—now point in the same direction: data-centre electricity demand is likely to at least double by 2030, with AI as the main driver. Water use is rising in parallel. Even aggressive efficiency improvements may not fully offset that growth.

- Terrestrial work-arounds are getting more exotic. From submerged data-centre ships to repurposed coal plants and co-location with nuclear reactors, the “easy” options—cheap land, cool climates, grid headroom—are being used up. The Drax conversion in the UK is unlikely to be the last of its type.

- Space is already part of the cloud story. Even if orbital data centres remaining niche, in-space compute will matter for sensors, communications and national security. Projects like Axiom’s ODC nodes are best seen as the top of a stack that already includes Starlink, Kuiper and other constellations acting as the cloud’s extended nervous system.

What orbital data-centre advocates are really arguing is that, as this stack grows, it may become rational to put at least some heavy compute directly where the power is—up there, not down here.

From cloud regions to galactic regions

If “galactic cloud regions” ever become more than a branding flourish, they will likely look quite different from the one-click regions in hyperscaler dashboards today.

The first genuine regions may be special-purpose:

- A cluster around a commercial station, serving high-value, high-security workloads.

- A co-located compute and storage layer for an Earth-observation constellation, doing in-orbit analytics before downlink.

- A power-first complex where AI training jobs that can tolerate higher latency are run directly on solar energy, scheduled to soak up otherwise “stranded” orbital generation.

They will be stitched into terrestrial clouds via laser links and ground stations, sold not as replacements but as additional zones with specific properties: extreme energy availability, different failure modes, and—if regulators allow it—distinct jurisdictional attributes.

In that sense, the move from cloud regions to galactic regions is less a sharp break than an extrapolation. For two decades, cloud computing has been about abstracting away geography while quietly exploiting its advantages. The only thing that has changed is the map.

The more urgent question is not whether we can build data centres in space. It is whether the incentives we are setting—through AI investment, energy policy and climate goals—make that outcome likely.

If the world continues to treat AI as a race in which compute is the main currency, then an orbit filled with solar-powered server farms is not the wildest possible endpoint. It is just one more reminder that our appetite for digital intelligence is starting to reshape not only our economies, but the infrastructure of near-Earth space itself.