After hydrogen leaks cut short the first attempt, NASA ran a full wet dress rehearsal on Feb. 19—loading the rocket, practicing the final countdown, and recycling the clock—then reported only minimal leakage at the most failure-prone interface.

Quick take

- What happened: NASA ended the Feb. 19 wet dress rehearsal at T-29 seconds after completing a planned recycle and reported minimal hydrogen leakage.

- Why it matters: NASA says it won’t set a launch date until it completes a successful rehearsal and reviews the data—this test is the gate for the first crewed lunar flight since 1972.

- What’s next: Engineering data review, then a go/no-go on whether March 6 (earliest) is realistic—or whether the program slips deeper into spring.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat NASA proved on Feb. 19

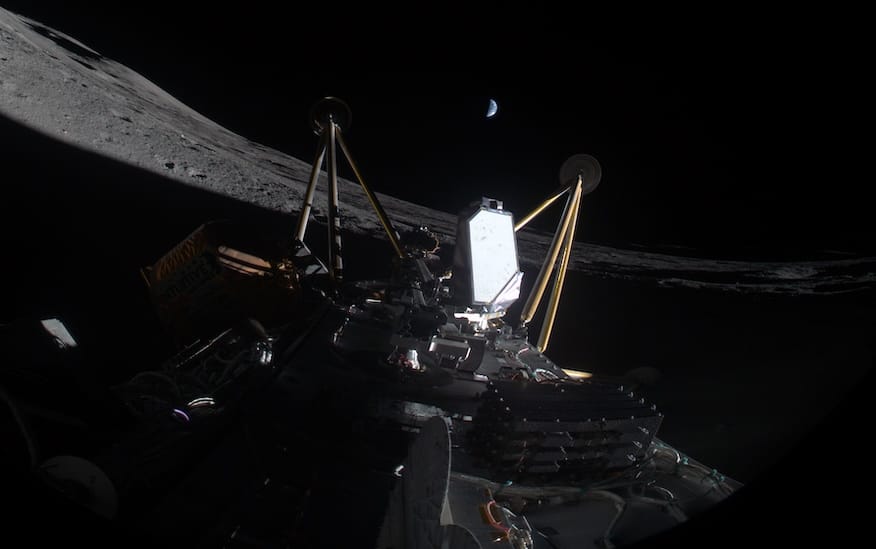

NASA’s Artemis II team wrapped its second wet dress rehearsal at 7:16 p.m. Pacific (10:16 p.m. Eastern), ending the simulated launch sequence at T-29 seconds—exactly where the test plan called for it to stop.

The rehearsal is deliberately repetitive and procedural: load cryogenic propellants, run the countdown deep into “terminal count” (the final automated phase), then practice a recycle—because on real launch days, the ability to safely scrub, reset, and try again is often the difference between a slip of hours and a slip of months. NASA’s live log shows the team executed the recycle sequence and even worked through a booster avionics voltage anomaly during terminal operations.

Most importantly, NASA said it saw minimal hydrogen leakage, staying within safety limits—after leaks forced a stand-down earlier this month.

The “hydrogen leak” problem, in one paragraph

Liquid hydrogen is a launch team’s frenemy: incredibly efficient as a rocket fuel, but hard to contain because the molecules are tiny, the hardware runs at extreme cryogenic temperatures, and the system relies on quick-disconnect interfaces that have to separate cleanly at liftoff. NASA describes the Artemis II trouble spot as the tail service mast umbilical connection between the mobile launcher and the rocket’s core stage—an area with multiple seals and plates that must remain tight while the system chills, flexes, and pressurizes.

Why this rehearsal is the real launch-date gate

NASA has been explicit: it’s “eyeing March”, but it won’t commit to a target launch date until a wet dress rehearsal succeeds and the data are reviewed.

That stance is shaped by the program’s recent history. On Feb. 3, NASA terminated the rehearsal at T-5:15 due to a liquid hydrogen leak at the tail service mast umbilical interface.

Since then, NASA says technicians replaced two seals around fueling lines after operators saw higher-than-allowable hydrogen concentrations, then ran a partial “confidence test” on Feb. 12 that was limited by a ground-equipment flow issue tied to a suspected filter.

Thursday night’s result—minimal leakage and a completed terminal-count recycle—suggests those fixes held under realistic conditions. AP reported teams loaded more than 700,000 gallons of supercold propellant and ran the countdown down to the half-minute mark, reset, and ran the final minutes again.

So… is March 6 actually plausible?

AP reported March 6, 2026 as the earliest potential launch date, with NASA still analyzing the rehearsal data to determine whether a March attempt is viable.

NASA’s own framing is slightly broader but still time-boxed: its Artemis II materials and live coverage position the flight as needing to occur no later than April 2026, and reiterate March as the earliest window.

A subtle confidence signal: AP reported the U.S.–Canadian crew prepared to enter a two-week quarantine starting Friday “to provide flexibility” inside the March window, and that some crew members monitored the test alongside the launch team.

Why the second attempt matters beyond Artemis II

Artemis II is the first time NASA will fly astronauts on SLS + Orion—Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and Canadian Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen—on a roughly 10-day out-and-back lunar flyby (no landing).

But the higher-stakes story is operational: if the program can’t turn around clean cryogenic load operations consistently, every later Artemis mission inherits a schedule risk that compounds. NASA’s administrator, Jared Isaacman, has already signaled he wants hardware changes—AP reported he’s pushing to redesign the rocket-to-pad fuel connections ahead of Artemis III.

What to watch next

- NASA’s data review + decision cadence: Whether NASA calls the Feb. 19 rehearsal “fully successful” after analysis—and how many residual work items remain.

- Pad-to-rocket interface health: Any reappearance of elevated hydrogen concentrations at the tail service mast umbilical during upcoming ops.

- Launch window discipline: If March slips, how quickly the schedule pressure runs into the “no later than April 2026” framing and downstream Artemis planning.