When the launch window opens on February 6, Artemis II will be the first time humans ride NASA’s Space Launch System. But the mission’s real deliverable isn’t a lunar flyby. It’s proof that the US can run a safe, repeatable deep-space industrial machine—at a price voters and lawmakers will keep paying.

On paper, Artemis II is a simple idea: four astronauts, one lap around the Moon, then home. In practice, it is a stress test of almost everything NASA has rebuilt since the Shuttle era—hardware, supply chains, procedures, and political patience.

This weekend’s rollout at Kennedy Space Center is the sort of spectacle that makes governments look competent: a 322-foot rocket-and-capsule stack, inching toward the pad on a crawler for a journey that can take most of a day. Then comes the wet dress rehearsal—loading more than 700,000 gallons of cryogenic propellant, running a trial countdown, and proving the team can safely drain it again if something goes sideways.

NASA’s own planning language gives away the mood. The Artemis II launch window opens “as early as” February 6. Readiness comes first; dates come second. The agency has already mapped three launch periods through early April, with specific opportunities sprinkled across each window—February 6, 7, 8, 10, and 11; March 6, 7, 8, 9, and 11; and April 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6—before range schedules, weather, and propellant logistics narrow the real choices.

That may sound like bureaucracy. It is also the point: Artemis II is a mission designed to prove that NASA can operate a system, not merely build one.

Table of Contents

ToggleArtemis II at a glance

- Mission: 10-day crewed lunar flyby to validate Orion’s systems with astronauts aboard

- Rocket: Space Launch System (SLS), Block 1; 322 ft tall; 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff

- Crew: Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Canada’s Jeremy Hansen

- Launch planning: roughly one week of opportunities followed by about three weeks of none, driven by trajectory constraints

Why this flight matters more than a lap around the Moon

NASA describes Artemis II as the first crewed mission on its path to a long-term lunar presence. The 10-day flight is meant to confirm that Orion’s systems operate as designed in deep space, with humans aboard.

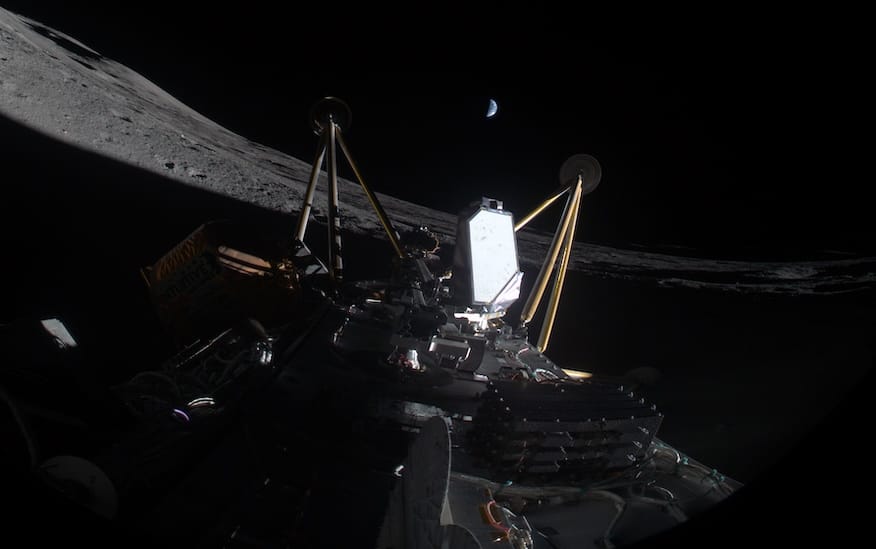

That sounds obvious—until you remember how long it has been since the US last sent astronauts beyond low Earth orbit. The last time, “deep space” was Apollo 17 in 1972. Artemis II is a return to that environment, but with modern expectations: continuous telemetry, complex software, new docking systems, and safety standards shaped by decades of lessons learned.

NASA itself says the crew will set a record for the farthest humans have traveled beyond the far side of the Moon. That is a neat headline. But the operational value is more concrete: Orion’s life support, power, thermal control, and navigation need to behave under real deep-space conditions—radiation, temperature swings, and time delays—not just inside a test chamber.

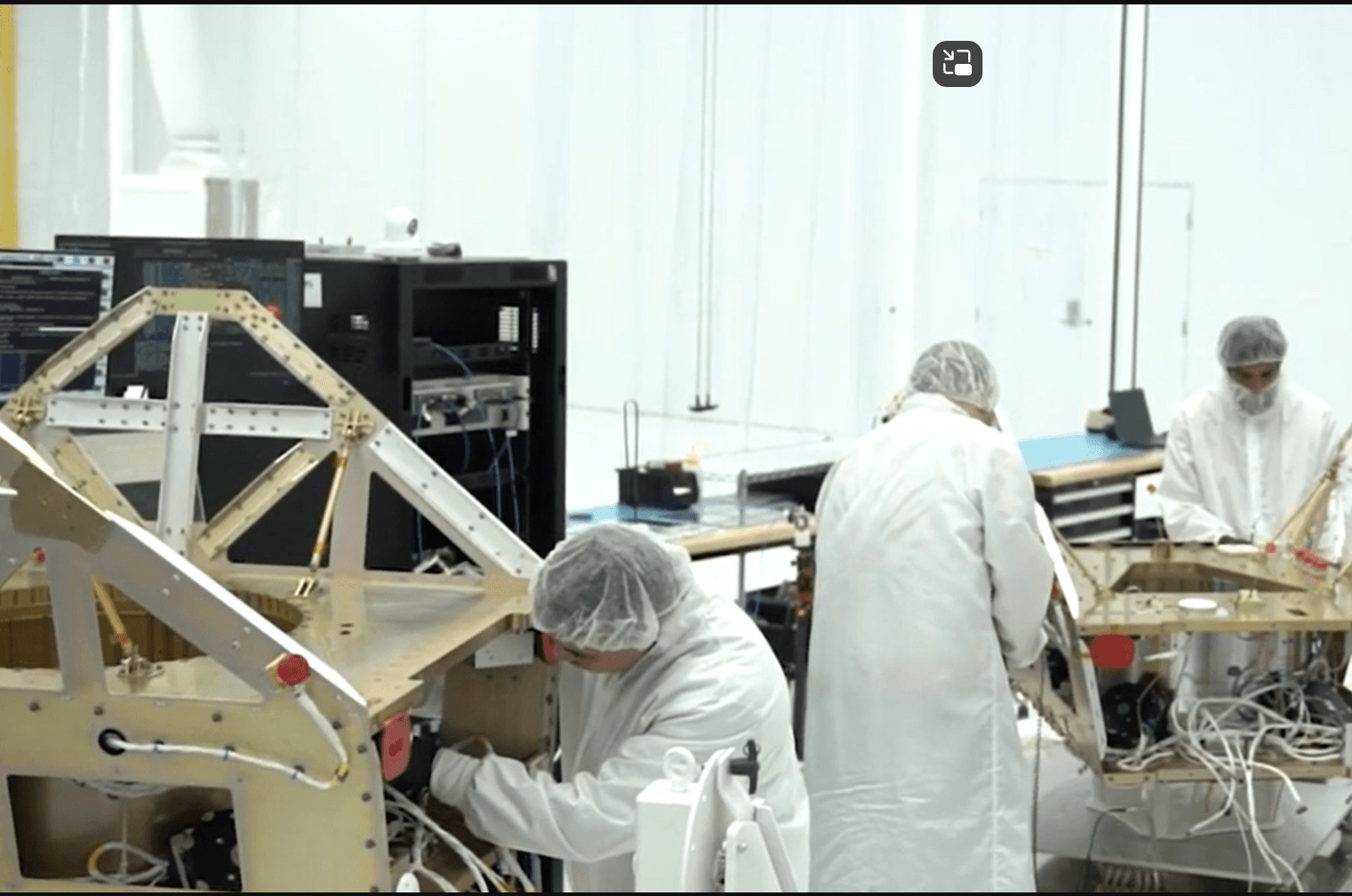

Artemis I, the uncrewed rehearsal in 2022, was a reminder that “mostly successful” can still generate long to-do lists. Orion traveled 1.4 million miles and hit Earth’s atmosphere at 24,581 mph on return. The capsule came back intact. But the flight surfaced issues that are now shaping Artemis II’s final countdown.

The heat shield problem that became a philosophy test

The highest-profile Artemis I surprise was Orion’s heat shield. NASA found unexpected “char loss”—material shedding in ways engineers did not predict. The agency says it identified the cause: gases inside the Avcoat ablative layer could not vent as expected during the “skip entry” return profile, leading to pressure, cracking, and pieces breaking off.

Two parts of NASA’s explanation matter.

First, it is not pretending nothing happened. NASA openly describes the physical mechanism and the test campaigns used to reproduce it, including arc-jet testing and a more accurate reconstruction of the flight environment.

Second, NASA’s mitigation for Artemis II is deliberately conservative: use the heat shield already attached to the capsule, but change the entry operations to keep risk acceptable. NASA also says that Artemis I data showed the crew would have been safe even if astronauts had been aboard, with internal cabin temperatures within limits.

This is what “test campaign” really means in public: you fly to learn, then decide what to change in hardware and what to change in operations. That is a reasonable engineering stance. It is also politically fragile. Every operational workaround invites the same question: why is an astronaut mission depending on a workaround at all?

NASA’s Inspector General put it bluntly in 2024: understanding and mitigating the heat shield’s root cause is “crucial,” and the Artemis I flight also raised other technical concerns that need mitigation before crewed flight.

The other risks are less dramatic — and more dangerous

Heat shields make headlines. Wiring and batteries decide schedules.

A NASA update in January 2024 said life support qualification testing had uncovered issues that required more time to resolve, explicitly framing crew safety as the driver of schedule changes.

The Inspector General’s May 2024 audit goes further: during qualification and acceptance testing, NASA found defects in Orion circuitry and crew module batteries that increase crew safety risk. Fixes involve hardware in difficult-to-access locations inside an already assembled spacecraft, and the battery investigation was still early at the time of the report.

The same audit reads like a checklist of why deep-space operations are unforgiving. It highlights risks tied to “limited operating life items”—components with time or usage limits that can become mission threats if schedules stretch. It even notes a practical constraint that sounds trivial until you picture the rocket: there is a limit on how many times the fully stacked vehicle can be rolled out to the pad.

In other words: delays are not free. They are measured in hardware life, workforce continuity, and real money.

Launch windows aren’t just astronomy; they’re systems management

NASA’s most recent Artemis II planning note is unusually transparent about why launch opportunities come in bursts.

To make the mission work, SLS must place Orion into a high Earth orbit first, where the crew and ground teams can evaluate life support before committing to the Moon. The timing then has to align for the trans-lunar injection burn and a free-return trajectory—one that uses the Moon’s gravity to send Orion home without needing major extra propulsion. The trajectory also must avoid keeping Orion in shadow for more than 90 minutes at a time, so the solar arrays can maintain power and temperatures remain within range.

This is not academic. The more constraints you stack, the more your schedule depends on not just rocket readiness, but also the mundane things: weather, propellant deliveries, and range availability. NASA says, as a general rule, up to four launch attempts may be possible within a given week of opportunities. In a program where each attempt is a major logistical event, that sentence is both practical and sobering.

The cost question Artemis II cannot avoid

Artemis II is a safety mission first. But it is flying inside an affordability argument that is getting sharper, not softer.

In 2021, NASA’s Office of Inspector General projected NASA would spend $93 billion on the Artemis effort from FY2012 through FY2025, and estimated the production and operations cost of a single SLS/Orion system at $4.1 billion per launch for Artemis I through IV. The audit argued that without reducing these costs, NASA would face “significant challenges” sustaining Artemis in its current form—especially because most of the stack is expendable, “single use,” unlike emerging commercial systems.

Independent groups put different numbers on different slices, but they point to the same reality: this is an extremely expensive way to buy lunar missions. The Planetary Society estimates that by the first test launch in 2022, SLS had cost $23.8 billion since 2011, Orion $20.4 billion since 2006, and related ground infrastructure $5.7 billion since 2012—about $49.9 billion combined across those buckets.

And overruns are not ancient history. GAO’s July 2025 highlights report says Orion alone accounted for over $360 million of annual cost growth, and that three Artemis projects account for nearly $7 billion of total overruns across major NASA projects since 2009. It also notes NASA has initiated nine new Artemis projects with estimated total costs over $20 billion, warning that interdependence can turn delays in one project into delays—and costs—in many.

Artemis II is therefore flying into a familiar Washington dilemma: the mission is technically justified, but the economic story needs to be defensible year after year.

The industrial base is the program — and the program is the politics

NASA’s rockets are also a jobs policy, whether anyone says it out loud or not.

Reuters reported in 2025 that SLS employs about 28,000 workers across roughly 44 states, a distribution that can translate into resilience on Capitol Hill. NASA itself has emphasized that all 50 states contribute to Artemis missions through companies and small businesses supporting SLS, Orion, and ground systems.

This wide footprint helps explain why Artemis is hard to reshape quickly. Programs that spread work broadly are harder to cancel, but also harder to streamline. Every redesign becomes a negotiation. Every schedule slip becomes a headline. Every cost spike becomes an argument about whether NASA is buying capability—or subsidising an industrial ecosystem.

That ecosystem is not standing still. NASA’s Inspector General estimates the SLS Block 1B upgrade (needed for later Artemis missions) will reach about $5.7 billion before a planned 2028 debut, driven largely by the Exploration Upper Stage. The same audit flags production quality and workforce issues as risks that can push schedules further.

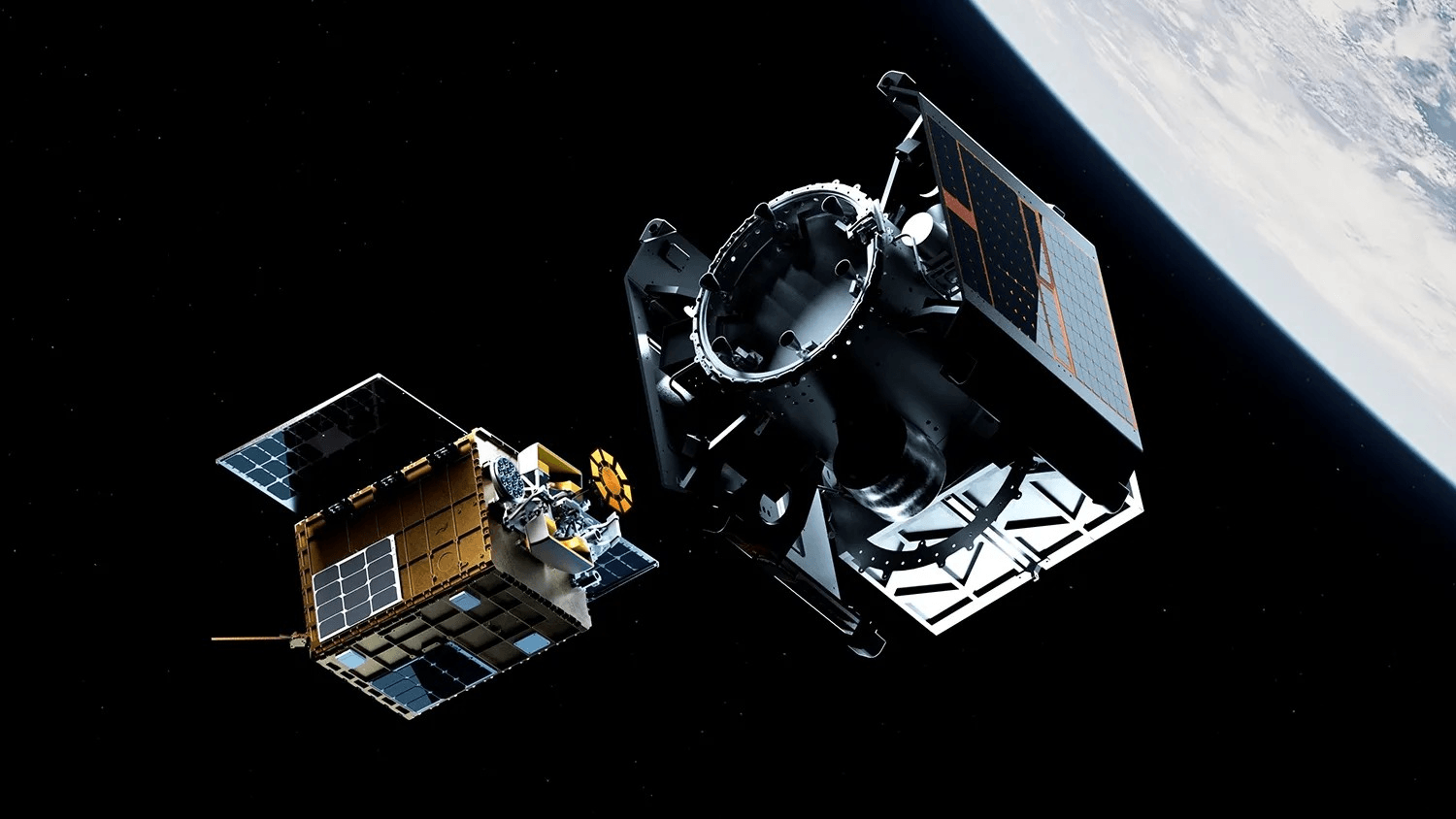

So Artemis II is not only about one flight. It is also about whether the broader machine can evolve while continuing to fly.

What success looks like — and what it buys NASA

For the crew, success is straightforward: Orion supports them, the systems perform, the spacecraft returns safely, and the program learns what it needs to learn.

For NASA leadership, success is more strategic. A clean Artemis II will:

- validate life-support operations in deep space with astronauts aboard, and reduce uncertainty ahead of a future landing attempt

- prove that the launch-and-recovery choreography—hardware, software, and teams—works end-to-end, not just in tests

- strengthen the political case that the US can execute deep-space human missions on a predictable cadence, rather than as a once-a-decade event

It is worth noting what Artemis II does not buy, even if it goes perfectly: it does not remove the need for a lunar lander, spacesuits, or other systems that sit outside SLS and Orion. NASA’s public Artemis III mission page currently lists launch “by 2028,” even as earlier NASA updates have described targets like mid-2027 depending on readiness.

That gap between aspiration and scheduling language is not a PR problem. It is the honest shape of a complex programme with many moving parts.

A thought to carry into the countdown

It is tempting to frame Artemis II as a symbolic return to the Moon. NASA’s own language, and the size of the rocket, invites that framing. SLS is taller than the Statue of Liberty and produces 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff—about 15% more than Saturn V.

But Artemis II is really a referendum on something more modern: whether the US can run a safe, repeatable, fiscally defensible deep-space transportation system in an era when “space” is no longer a slow monopoly.

NASA keeps saying it will let “readiness and performance” dictate the launch date. That is the correct sentence to say before you put humans on a new rocket. It is also a sentence that quietly admits what everyone in the program already knows: the hardest part of going back to the Moon is not the physics. It is the discipline of doing it again—and again—without losing public trust along the way.