Europe just did something it has long resisted: it placed institutional launch orders with a privately funded startup. Under the European Space Agency’s (ESA) new Flight Ticket Initiative, ESA and the European Commission have awarded two missions to Germany’s Isar Aerospace and three to Italy’s Avio—the first time European institutions have bought launch services from a venture-backed provider on the continent. It’s a small procurement on paper; strategically, it’s a pivot.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat was actually awarded—and to whom

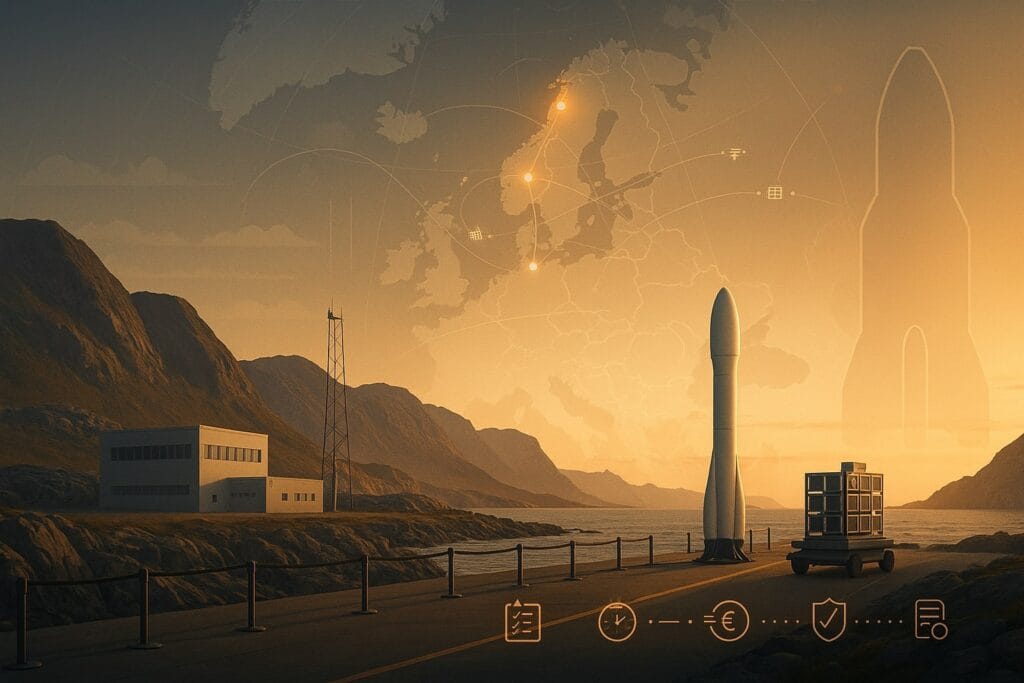

ESA’s announcement confirms five initial “Flight Ticket” missions: three rideshares on Vega-C managed by Avio out of Kourou, and two dedicated flights on Isar’s Spectrum launcher from Andøya Spaceport in Norway. Payloads named so far include:

- Persei’s E.T. Pack, a kilometre-long tether to deorbit satellites using Lorentz drag;

- DLR’s Pluto+ CubeSat, demonstrating compact avionics and 100-W flexible solar arrays;

- Grasp’s GapMap-1, a SWIR spectrometer to detect greenhouse gases;

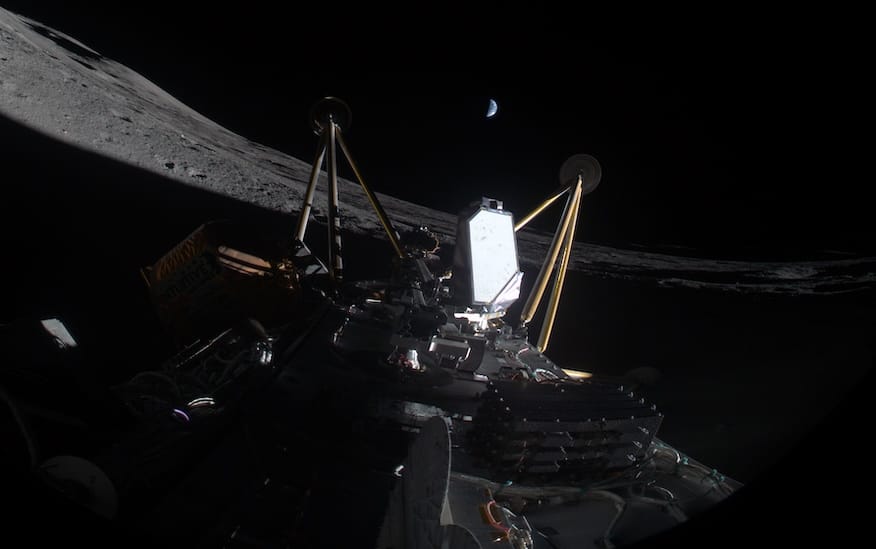

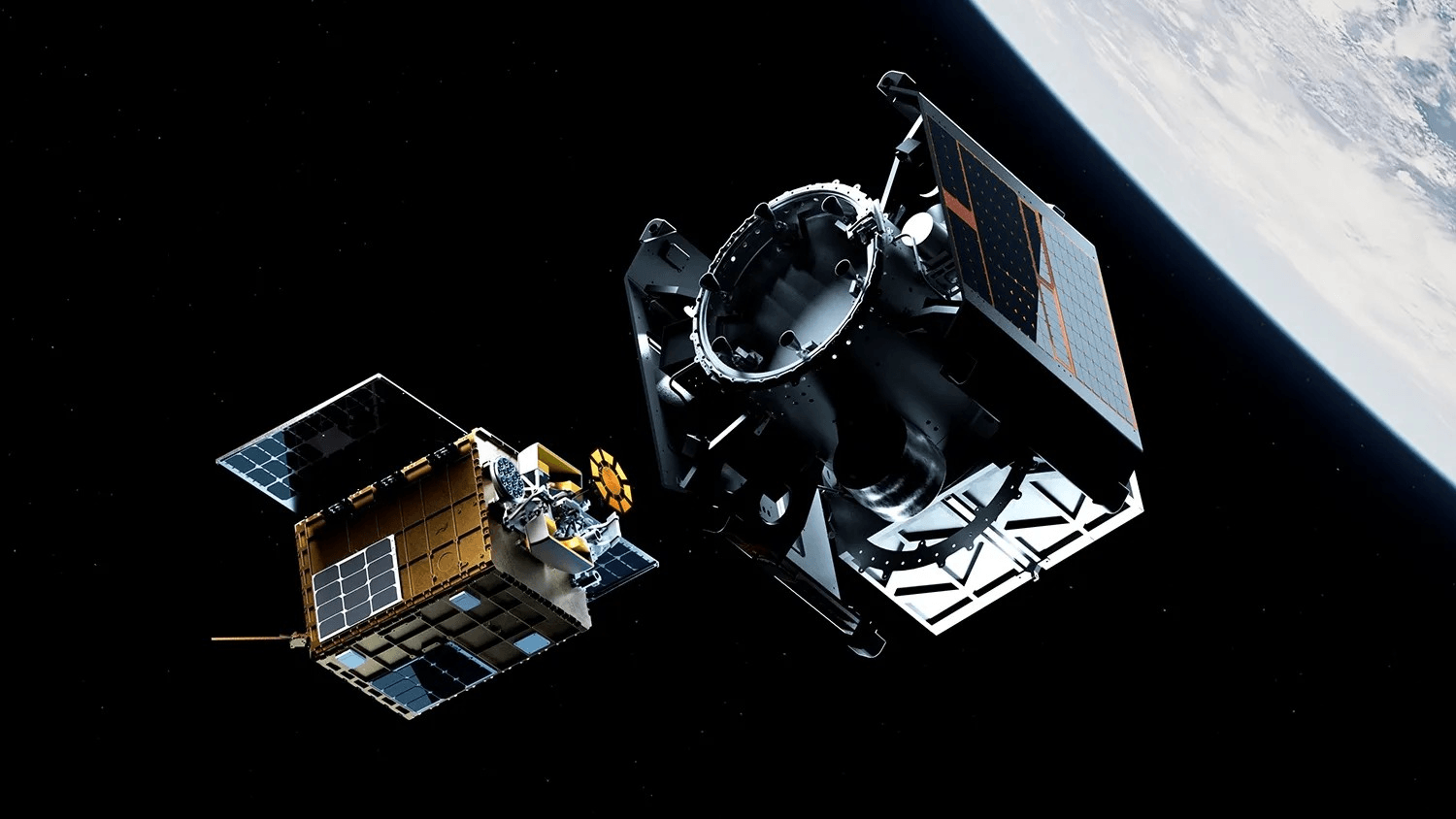

- Infinite Orbits’ “Tom & Jerry” two-sat mission to rehearse close-proximity debris servicing;

- ISISPACE’s “CASSINI” cubesats, aggregating multiple experiments.

These tickets are explicitly designed to give “ready-to-fly” technology a European ride—on European-built launchers—with co-funding from Horizon Europe and ESA’s Boost!. The next selection cut-off is 1 October 2025. (ESA release; European Commission programme page).

Isar’s own note stresses the headline first: it is, by its telling, “the first privately funded European launch service provider” to sign such institutional agreements with ESA and the Commission, with missions from 2026 onward. Treat that as a claim—but one that aligns with how Flight Ticket is structured.

Why this is different from past ESA buys

For decades, Europe’s institutional payloads rode on Ariane or Vega via Arianespace—systems born of public-industry consortia and stitched together through “geo-return” politics. Flight Ticket injects a competition-based procurement stream specifically to create regular, affordable, and responsive launch opportunities—without forcing every mission into a legacy launcher or a single spaceport. Just as important, the Commission makes clear this mechanism exists to stimulate new European launchers and diversify providers, not merely fill manifest gaps.

The distinction matters for what comes next. ESA has already signalled a willingness to loosen traditional constraints elsewhere: its LEO Cargo Return programme is set to proceed without geo-return in Phase 2—read: best athlete wins—pending ministerial approvals. If that posture generalises, today’s modest Flight Ticket buys could be the opening notes of a broader shift from entitlement to performance across Europe’s launcher policy.

The Andøya factor: a new northern node for institutional access

Both Isar missions are slated to launch from Andøya, not Kourou. That’s a structural change: Norway’s spaceport is licensed for up to 30 launches per year (only one pad exists today, used exclusively by Isar), offering Europe geography, weather windows and range control that aren’t dependent on South America. Following Isar’s NCAA operator licence in March, and despite the 30-second first-flight failure later that month, the pad remained largely intact and the cadence ambitions stand. In other words: Flight Ticket is backing a site and a supply chain, not just a rocket.

Andøya’s rise is also part of a wider Nordic storyline. Esrange (Sweden) is positioning to fly orbital missions, with fresh political attention on Arctic spaceport rivalry and cooperation. For institutional buyers, multiple European ranges reduce scheduling risk and create negotiating leverage on price and cadence.

Who really benefits—and who should worry

The immediate winners are obvious:

- Avio gets three Vega-C rideshare slots, underscoring the vehicle’s role as Europe’s multi-payload workhorse while Ariane 6 ramps.

- Isar Aerospace gets two institutional references to anchor a post-demo manifest.

But the downstream effects are broader. The Commission lists a current pool of European launch providers eligible for Flight Ticket competitions—not just Avio and Isar, but Orbital Express (UK), PLD Space (ES), and Rocket Factory Augsburg (DE)—with additional framework agreements reported with Arianespace, PLD, Orbex, and RFA last year. Expect follow-on awards once more payloads hit “ready to fly” status.

The incumbent to watch is ArianeGroup. If small and medium payloads can now ride via competitive tickets (Isar, PLD, RFA, Orbex) or Vega-C rideshares, Ariane 6 will likely concentrate on heavier government payloads and commercial GEO/LEO constellation contracts—but under more price pressure from SpaceX and, soon, Vulcan. Europe’s launch monopoly era has already ended; Flight Ticket accelerates the segmentation of the market. (Contextual analysis; see official programme documentation for scope.)

Procurement as industrial policy—now with metrics

What Europe is testing here isn’t just rockets. It’s a procurement model:

- Purpose: de-risk in-orbit demonstration/validation (IOD/IOV) for European tech, build flight heritage faster, and stimulate manufacturing scale among new launch entrants.

- Mechanics: co-funded launch slots, open calls with regular cut-offs (next on 1 Oct 2025), and exclusive use of European-made launchers.

- Intended outcomes: increased availability, responsiveness, and price discovery across a portfolio of providers and ranges.

If ESA/Commission publish per-mission KPIs—turnaround times, cost bands, integration lead times—Flight Ticket could become Europe’s VADR-like channel for agile launch buys, with data rather than political allocation guiding future awards.

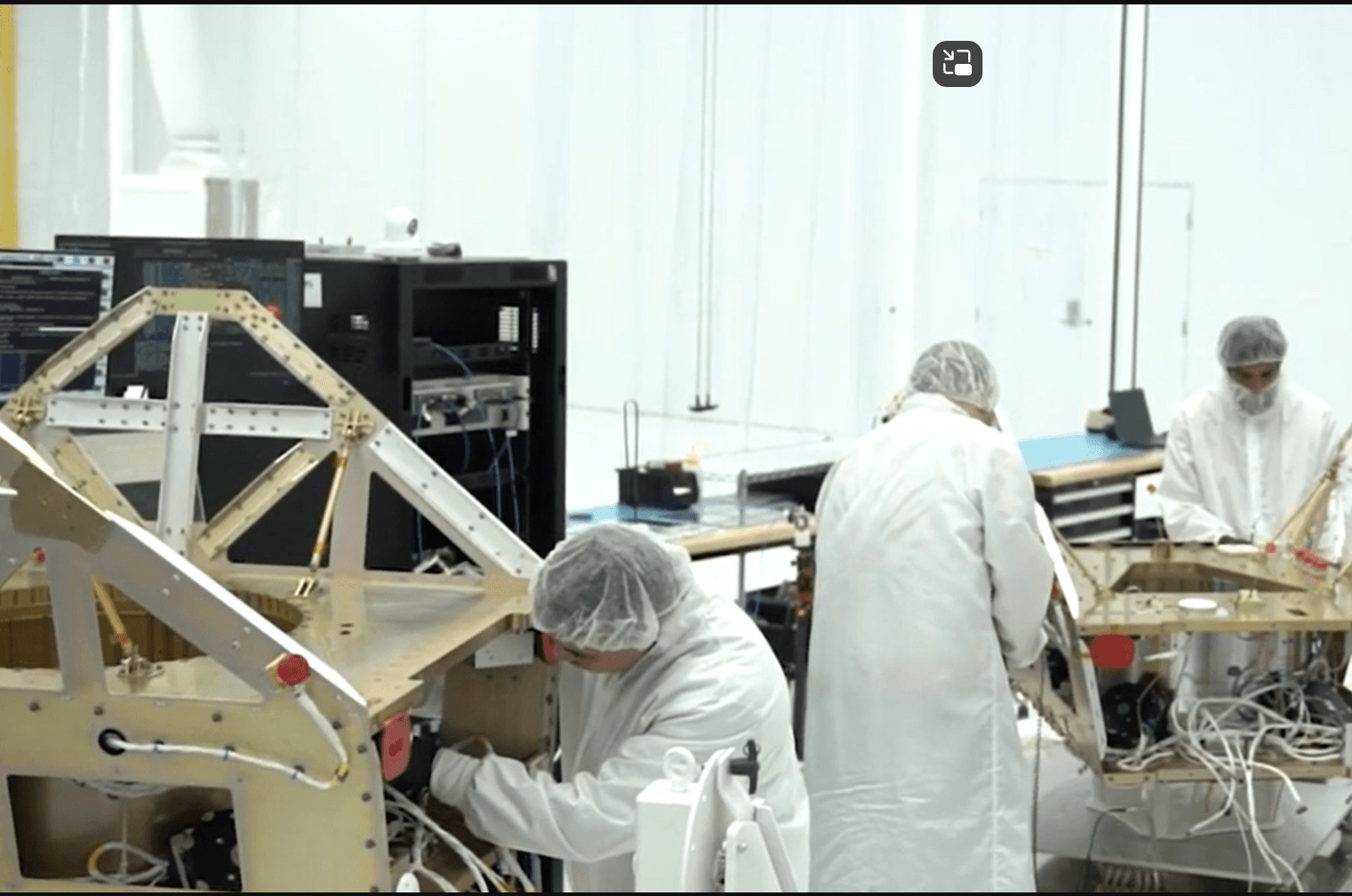

The Isar question: can a startup carry institutional load after a failed first flight?

It’s the obvious concern. Isar’s Spectrum reached only ~30 seconds in its 30 March debut, then was terminated, with the pad largely unharmed. In the US, NASA’s VCLS/VADR frameworks absorbed similar early-flight outcomes from multiple startups and still produced reliable services within cycles. Europe is, in effect, importing that learning curve: buy early, couple payments to milestones, and let competition and iteration do their work. Isar says the two Flight Ticket missions begin from 2026, giving time for return-to-flight, qualification, and range throughput growth.

For institutional customers, the risk calculus is more favourable than it looks: payloads are tech demos with high learning value, insurance pools are accustomed to early-stage launcher risk, and rideshare/dedicated mix widens path-to-orbit options if retargeting is required. (Programme architecture per Commission/ESA documents.)

A quietly competitive field is forming

Flight Ticket sits alongside ESA’s European Launcher Challenge (ELC), which has pre-selected five challengers—Isar, MaiaSpace, Orbital Express Launch, PLD Space, and Rocket Factory Augsburg—eligible for up to €169m each (combining service delivery and capacity-upgrade demos), subject to a ministerial in late 2025. That parallel track matters: Flight Ticket buys near-term rides; ELC aims to scale supply with multi-year funding and institutional missions.

If ELC money flows without heavy geo-return strings—as ESA hints on LEO cargo—the cost curve for European launch should bend down faster. If not, startups will still win tickets, but the industrial impact will be slower and patchier.

Andøya vs. Kourou vs. Esrange: Europe’s multi-range future

The geography is policy. Kourou remains essential for Vega-C (and Ariane 6), but Andøya offers high-latitude inclinations and European regulatory control. Esrange adds depth—plus political incentive as Nordic capitals lobby for autonomy from non-European ranges. For operators and satellite customers, this multi-range competition can tighten integration timelines and cut weather/range slip risk—key drivers of effective cost per kilogram even before sticker price.

What to watch next (next 6–12 months)

- Return-to-flight milestones at Andøya: static fires, FAA-style readiness reviews (via Norway’s CAA), and pad availability windows. (Permitting & capacity references.)

- October 1 Flight Ticket cut-off: which “ready-to-fly” missions enter the pool; whether additional launch providers are added to the eligible set.

- ELC ministerial decisions (late 2025): amounts, winners, and any geo-return caveats that would dilute “best-athlete” competition.

- Vega-C cadence: Avio’s ability to absorb more auxiliary payloads without manifest congestion will shape whether Flight Ticket keeps leaning on rideshare vs. small-launcher dedicated flights. (Programme and award mix per ESA.)

Bottom line

Europe has finally put real money behind a principle the US proved a decade ago: buy services, not hardware—and buy them from whoever can perform. Flight Ticket’s first orders are modest. But by sending institutional payloads to a startup’s pad in Norway, ESA and the Commission have de-risked a new market channel, signalled a post-geo-return mindset, and created incentives for price, cadence, and reliability to improve on a European timetable. On current evidence, that’s exactly the point.