Europe has finally done what many in the industry said was inevitable. On Thursday, October 23 (Pacific), Airbus, Thales and Leonardo said they will fold major satellite manufacturing and services units into a single company—code-named Project Bromo—with operations targeted to begin in 2027, pending approval. The new group would bring together Thales Alenia Space, Telespazio, selected Airbus Space & Digital assets, Leonardo’s remaining space units and Thales SESO, creating a Toulouse-based champion with about 25,000 staff and €6.5 billion in annual revenue (based on 2024 figures). The share split: Airbus 35%, Thales 32.5%, Leonardo 32.5%. Management expects “mid–triple-digit” millions of euros in synergies starting about five years after close.

The European Space Agency reacted within hours, saying it will study the implications for competitiveness before adjusting procurement policy—an early sign that regulatory and policy gating will matter as much as engineering. ESA’s director general said the move can strengthen Europe, but it will “change the landscape” and must be weighed against the interests of taxpayers and a healthy supplier base.

Why this is happening now

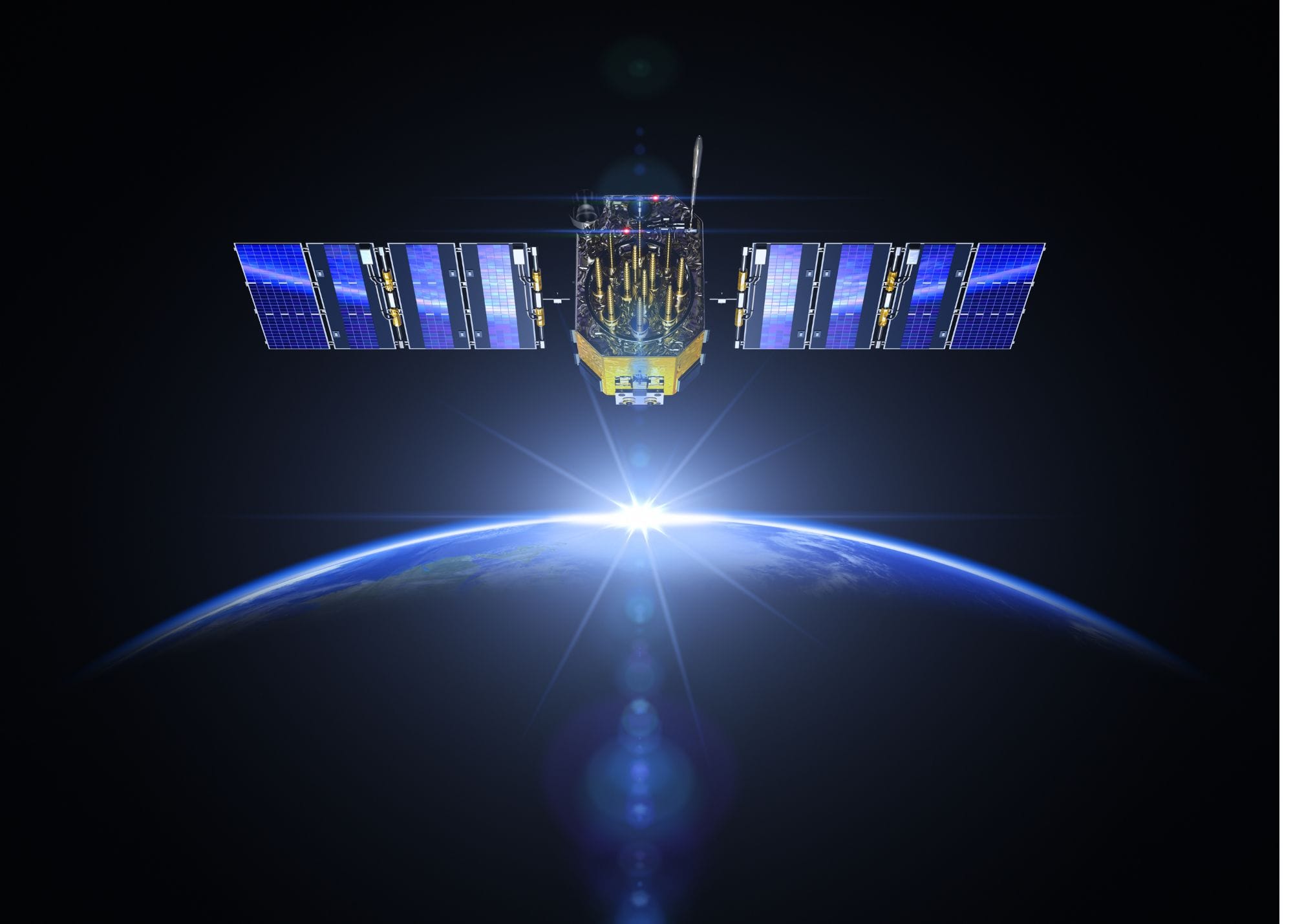

Two forces pushed Europe to move. First, LEO economics have tilted competition away from bespoke GEO builds and towards scalable product lines and software-defined payloads—domains that reward platform commonality and high-tempo integration. Second, sovereignty: Europe has leaned on SpaceX for a significant slice of launch and connectivity in recent years, a discomfort that has animated everything from Ariane 6 ramp plans to the IRIS² secure-comms constellation. Policymakers and investors alike have warned that over-reliance on U.S. platforms is a strategic risk; creating a single “prime” is the industrial policy answer.

There is also a practical precedent. The cooperation model resembles MBDA—the pan-European missile group formed in 2001—signalling that governments want a structure that can bid coherently on sovereign programmes while promising fair work-share and stable governance. The companies explicitly referenced that lineage in framing the deal.

What exactly is being merged

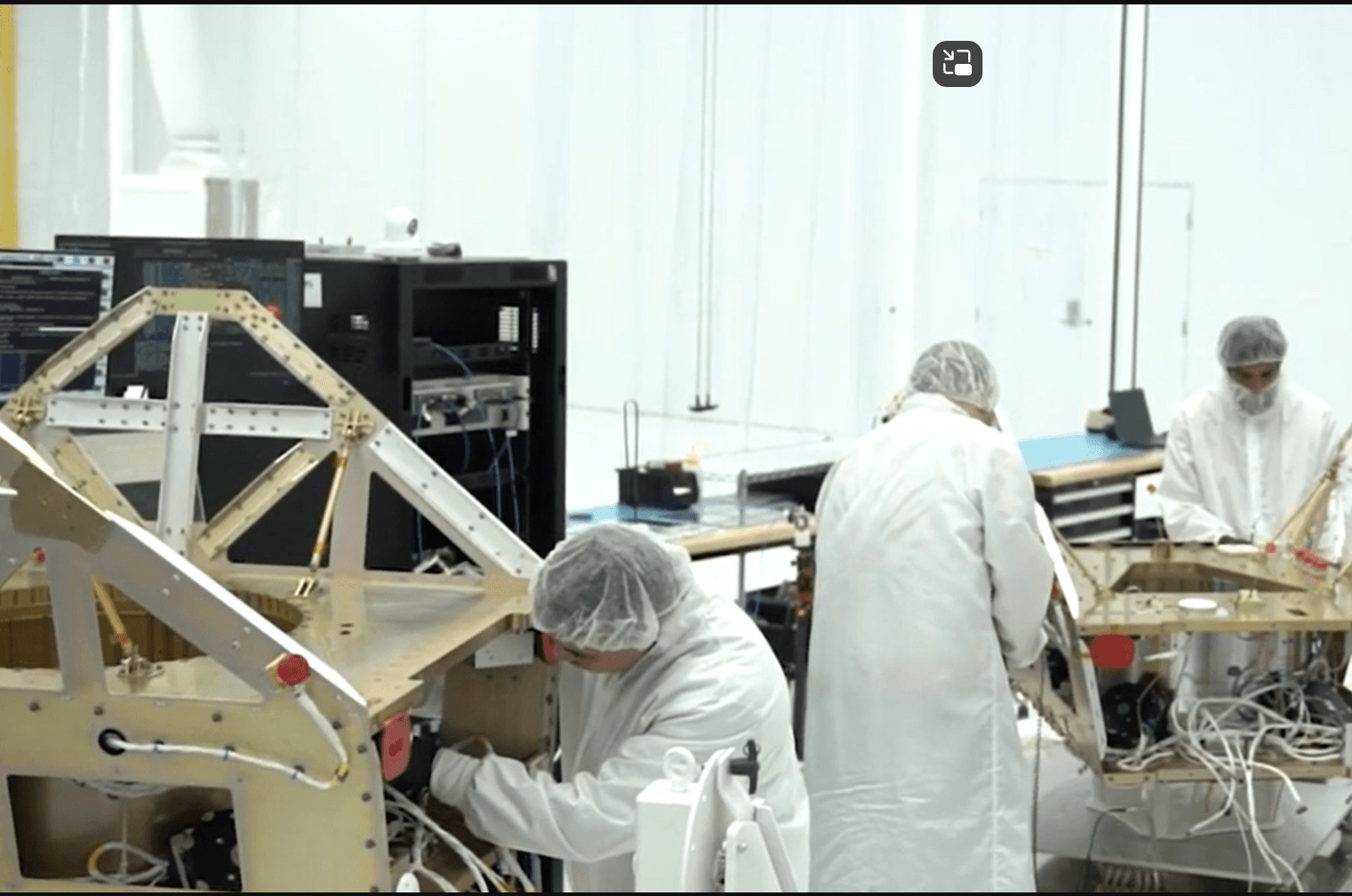

Beyond the headline names, the combination matters because of what sits inside:

- Thales Alenia Space (prime manufacturer) and Telespazio (satellite services & ground), the Franco-Italian JVs at the heart of Europe’s GEO, EO and exploration heritage.

- Airbus Space & Digital businesses that design and integrate spacecraft buses, payloads, constellations and ground systems.

- Leonardo’s residual space activities and Thales SESO (optics), completing a stack that spans hardware, software and operations.

The group will be headquartered in Toulouse, with a formal governance framework to be hammered out before close. Management has downplayed the idea of rotating leadership by nationality—an approach that caused friction in earlier European aerospace structures—and has not announced new layoffs beyond reductions already executed.

The strategic bet: make standards the moat

Scale alone won’t beat Starlink-era competitors. The defensible advantage is standardisation across buses, avionics, optical links and ground software—plus an industrial cadence that looks more like product, less like project.

- Fewer, more modular platforms. Expect a rationalised catalogue of small, medium and large buses with common avionics, power, thermal and in-orbit software interfaces. That lowers non-recurring engineering and makes multi-mission payload swaps viable late in the build.

- Ground stack unification. A common TT&C and mission-planning layer turns once-off projects into repeatable service operations—the stickiest part of the P&L.

- Procurement leverage. A single prime can commit to multi-year component buys (star trackers, reaction wheels, OISL terminals), pulling unit costs down and shortening lead times—critical in LEO replenishment cycles.

That playbook—standards + cadence—is how this venture aims to regain cost and schedule credibility in a market where customers now benchmark against SpaceX-rate iteration.

Who wins (and who won’t)

Winners

- Subsystem specialists with dual-source capability—think optics, propulsion modules, power electronics—who can feed standard platforms at volume.

- Service operators that want turnkey, multi-orbit packages. European governments are exploring secure-satcom procurements ahead of IRIS² coming online; a unified prime can bundle GEO/LEO capacity and managed services.

- Export customers that value end-to-end sovereignty options (payload + platform + ground), not just spacecraft.

Likely losers

The regulatory and policy gate

Two processes run in parallel:

- EU competition review. Previous attempts at consolidation struggled here; remedies could include divestitures, behavioural commitments on fair access to standard platforms, or open interfaces for third-party subsystems.

- ESA industrial policy. ESA says it will adapt procurements to preserve competition. That could mean lotting large programmes to ensure multi-vendor participation, or mandating dual-source critical components. Either path shapes the eventual moat: strong standards, but with regulated on-ramps for challengers.

The sovereignty read-through

Analysts are blunt: this is a sovereignty play as much as a commercial one. The timing coincides with European capitals re-evaluating dependence on U.S. launch and U.S.-controlled broadband constellations for government traffic. Italy’s recent stop-start flirtation with Starlink for secure communications, and Brussels’ push to accelerate IRIS², are part of the same story. The new prime is designed to be the trusted counterparty on those sovereign contracts.

Integration risk: five years is a long time in LEO

The companies are guiding to synergies after year five—sensible for a merger of this size, but risky in a market that resets technology every 18–24 months.

- Execution: harmonising PLM systems, QA regimes and supplier frameworks across France/Italy/Germany/Spain is non-trivial.

- Cadence: customers will judge the new prime on 12- to 18-month delivery rhythms, not on one-off flagship builds.

- Talent: integration fatigue is real—keeping flight heritage teams intact while adopting product discipline is the cultural pivot.

The Ariane 6 ramp will help—or hurt—perception. A visible European launcher cadence paired with a unified spacecraft catalogue is the brand the continent wants to project. Without it, the narrative snaps back to the U.S. (SpaceX) or, increasingly, to commercial Asian entrants.

For investors: the working model to underwrite

- Revenue baseline: ~€6.5 bn on 2024 figures across manufacturing, ground, and services; growth tied to sovereign secure-comms, Earth-observation refresh, and exploration logistics.

- Synergies: “mid–triple-digit” millions after five years, mostly procurement and SG&A; the upside is productisation (platform reuse), not headcount.

- Policy tailwinds: IRIS² ramp and national secure-satcom buys in Italy and elsewhere provide near-term demand hedges while commercial orders normalise.

- Macro headwind: Europe contributed ~10% of global public space funding last year; if that share doesn’t rise, the new prime must take wallet share from incumbents or win exports to hit growth targets.

What to watch next (next 90–180 days)

- Governance details. “Joint control” contours, board composition, and how programme P&L will be measured. (A clue to whether product cadence or national work-share wins day-to-day.)

- Procurement signals. ESA/EU tenders that specify standard bus families or open interface requirements—both would validate the standards-as-moat thesis.

- Customer posture. Watch statements from Eutelsat (and other anchor customers) about price/performance improvements; also watch objections or appeals from OHB and national ministries.

- Early product markers. A unified small-sat bus with common avionics shipping across EO and communications inside 18 months would be the tell that integration is working. (If not, expect slippage and bespoke back-sliding.)

- IRIS² milestones. Contracting cadence, hardware awards and the first integrated ground demonstrations.

Bottom line

Project Bromo doesn’t just create a bigger balance sheet. It creates the conditions to standardise how Europe builds and operates satellites—and that is the only sustainable moat in a Starlink-calibrated market. If Brussels and ESA calibrate the rules well—open standards, real competition inside a standardised stack—the continent gets a globally competitive prime and a healthier supply chain. If not, Europe risks trading the old problem (fragmentation) for a new one (complacency).

For now, the opportunity is in sight. The next six months of governance and procurement choices will decide whether Europe’s new prime learns to ship like a product company—or remains a federation of projects with a new logo.