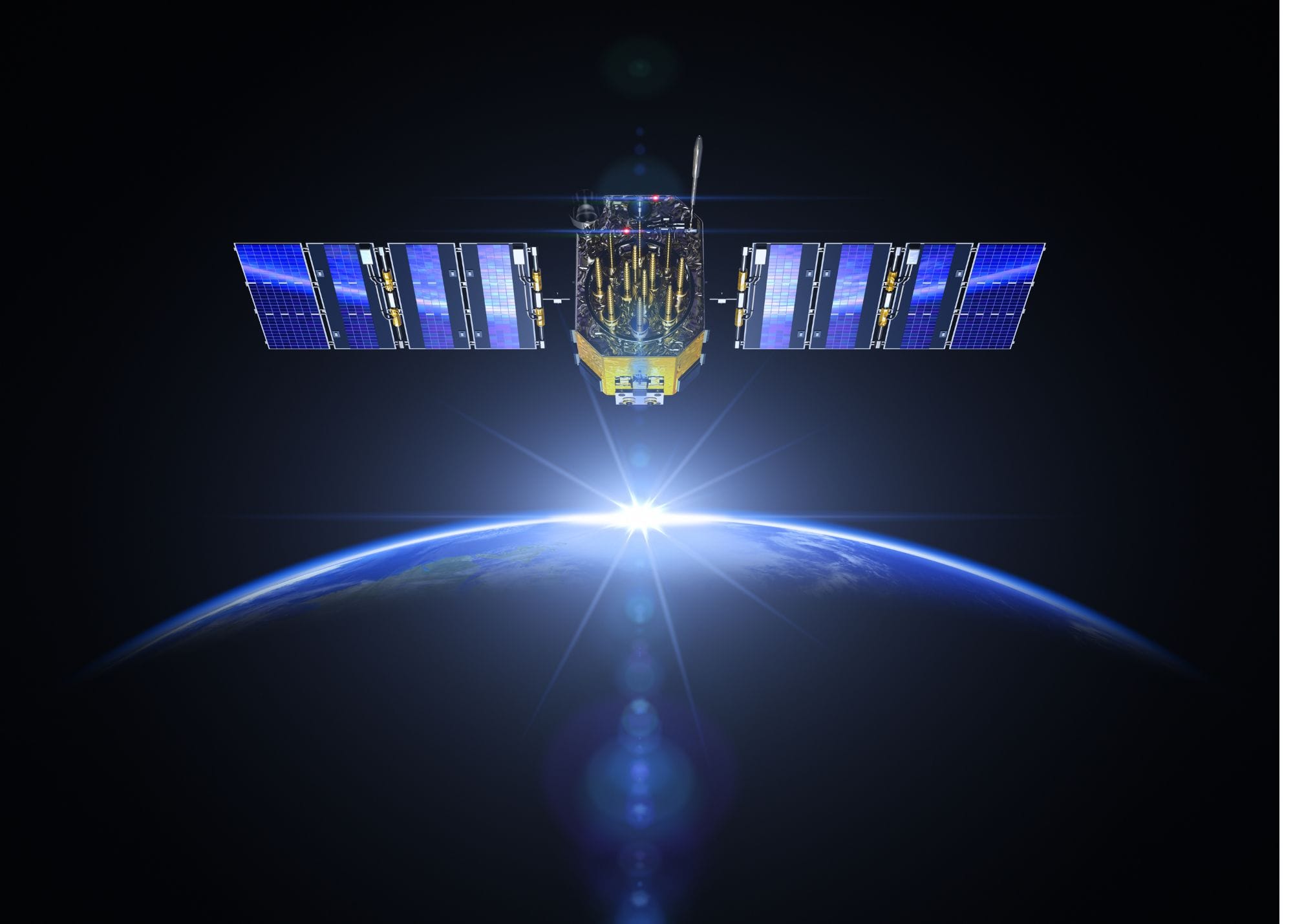

Hanoi has done something unusual for a tightly managed telecoms market: it’s inviting two U.S. giants to compete, at speed, under a five-year pilot that rewrites how satellite internet is regulated, built and sold in Vietnam. The result will test whether LEO can complement one of Asia’s most aggressive fibre rollouts—and whether Washington–Hanoi trade politics now run through space.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe spark

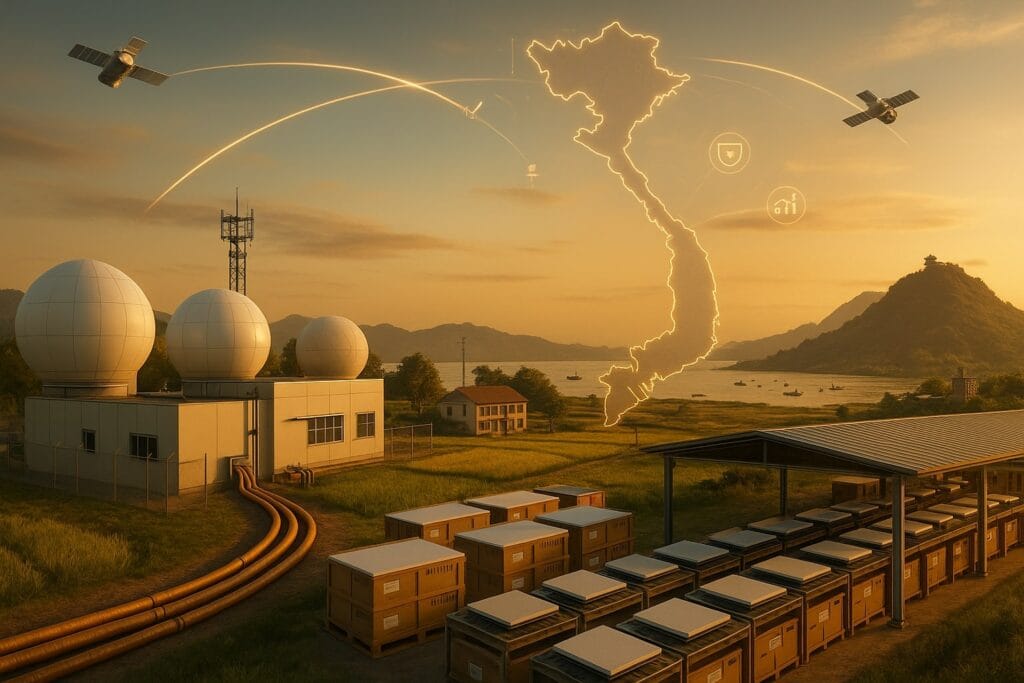

On August 27, 2025, Vietnam’s Ministry of Science and Technology disclosed that Amazon aims to deploy Project Kuiper in Vietnam, pledging up to six ground stations and local terminal manufacturing in Bac Ninh by 2030, via partnerships and a newly formed Amazon Kuiper Vietnam Co., Ltd. Kuiper has already filed for a pilot service and wants to target underserved rural and island areas across consumer, enterprise and government segments.

This comes weeks after officials said SpaceX’s Starlink is expected to begin a pilot in Q4 2025, contingent on establishing a wholly owned local subsidiary and completing investment procedures—part of a government-backed trial that runs until 2030.

Taken together, Vietnam has set the stage for a LEO broadband battleground in 2025–2030, with both players pushed to localize infrastructure and align with sovereign requirements rarely seen elsewhere.

The policy pivot that made this possible

Vietnam’s move rests on two pillars.

- A controlled LEO pilot scheme (Decision 659/QĐ-TTg, Mar 27, 2025): It permits nationwide pilot services for fixed and mobile satellite access, caps total subscriptions at 600,000 during the trial, and—crucially—lets foreign firms operate via 100%-owned Vietnamese entities. The trial window lasts five years from the local company’s establishment, but must end before Jan 1, 2031.

- Gateway sovereignty requirements (Decree 163 and draft rules): All traffic from satellite terminals must pass through a gateway on Vietnamese territory connected to the public network, and foreign providers must have a commercial agreement with a licensed domestic telecom enterprise. The draft added minimum capital thresholds and enforcement provisions; Decree 163, effective 2025, codified the gateway rule and competition safeguards.

In plain English: Vietnam will take LEO—but on Vietnam’s terms. That means local ground infrastructure, lawful intercept capability, emergency cut-off, user identification, and integration with domestic carriers.

Why now? Industrial policy, not just internet policy

The timing is not accidental. In early 2025, Hanoi faced the risk of U.S. tariffs on its rising trade surplus. Easing the way for Starlink’s pilot and now Kuiper’s entry was read as an “olive branch” in that geopolitical negotiation, alongside cuts to U.S. import tariffs. Space internet, in this context, is also diplomacy.

At home, Vietnam is racing to blanket the country with fibre (policy goal: 100% of households to have fibre access by 2025) and 5G. But fibre and towers don’t fully solve mountainous provinces or offshore islands. The government’s own data shows mobile coverage reaches ~99.8% of people but far less of the land and maritime area, leaving gaps that LEO can fill for schools, clinics, fisheries, border posts and islands.

The commercial stakes

Starlink’s head start

Starlink already operates across ASEAN—Philippines (since 2022), Malaysia (since 2023), and Indonesia (2024)—often entering with health/education pilots and quick rural uptake. That regional traction, plus millions of global users, gives Starlink brand recognition and a field-proven kit. Vietnam’s pilot targets a Q4 2025 start once the subsidiary is in place.

Kuiper’s localisation play

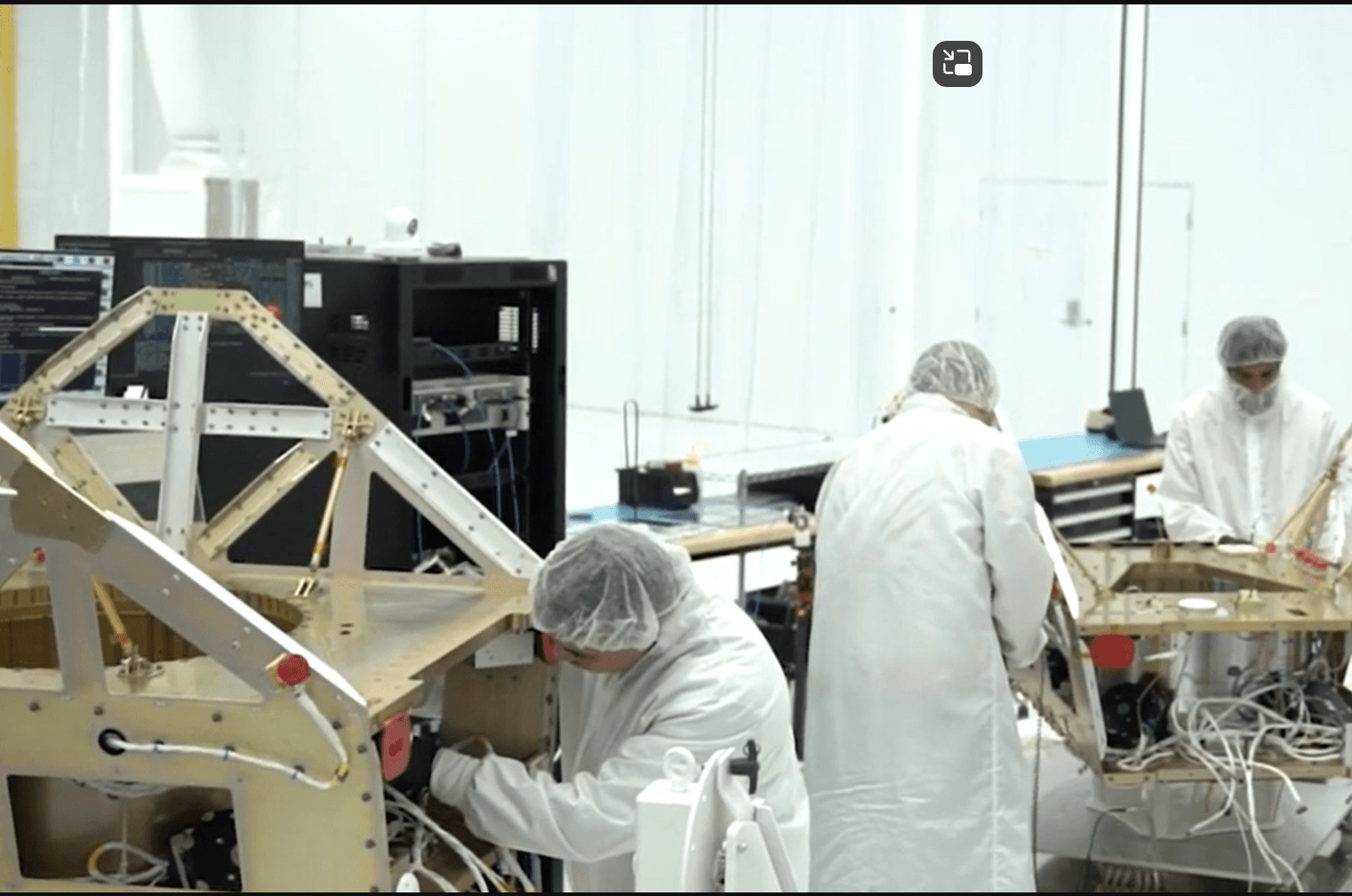

Amazon’s offer leans into local industrial capacity: ground stations and terminal manufacturing in Bac Ninh, a northern electronics hub. If executed, Vietnam could become a regional terminal base for Kuiper, aligning with Hanoi’s push to climb the electronics value chain. And Kuiper’s announced terminal family—~400 Mbps “standard” unit produced for < $400; a 7-inch, ~100 Mbps low-cost unit; and a 1 Gbps pro dish—sets hardware economics that could resonate in price-sensitive markets if local assembly trims logistics costs and import duties.

Backhaul and enterprise may be the real prize

The pilot explicitly allows leased channels for mobile station transmission (i.e., cellular backhaul), not just household internet. With Vietnam pushing 5G coverage and fibre to every commune, LEO backhaul can reduce rollout friction in hard-to-reach areas, supply temporary capacity for events/disasters, and serve maritime/aviation, logistics and energy clients. Expect Viettel, VNPT and FPT to show up as resellers/integrators under the “commercial agreement” model the decree requires.

Vietnam isn’t a “blue ocean”—and that’s the point

The country already has one of the world’s most ambitious broadband agendas. By official targets, all 27 million households should have access to fibre by 2025, and fibre adoption already exceeds 80% of households. LEO won’t displace fibre; it fills the last 10–20% of geographies where fibre is uneconomic or too slow to deploy. Think islands, mountain communes, fisheries fleets, border roads, and backup links for hospitals and schools.

That means the consumer TAM for residential LEO may be bounded by fibre’s success and mobile bundle economics. But enterprise/government, mobility, and carrier backhaul could be sizable—and strategically important.

Unit-economics reality check (without speculative pricing)

- Hardware: Starlink’s kit varies by market; Kuiper’s stated manufacturing cost targets (< $400 for the standard terminal) hint at an ability to price competitively once volume ramps. Vietnam-based assembly could shave VAT/import and logistics costs. (Amazon has not published Vietnam retail pricing.)

- ARPU: ASEAN examples suggest consumer pricing must match local income levels. Vietnam’s regulators will watch affordability—and may prefer LEO as wholesale backhaul and public-service connectivity during the pilot, where impact per dollar is highest. (Philippines/Indonesia references show wide ARPU ranges, but are not a basis for Vietnam pricing today.)

- Scale: The 600,000-subscription cap during the pilot creates scarcity that favours B2B/B2G and backhaul early on. Providers will chase high-value verticals and anchor tenants before mass-market retail.

What Vietnam got right (and why others should study it)

- Sovereign control with innovation on-ramp

The gateway-in-country mandate and 100% foreign ownership pilot protect security while giving operators clear rules. Providers know what to build; the state retains levers for lawful access and shutdown. - Industrial capture, not just service import

By nudging local ground stations and terminal manufacturing, Hanoi captures capex and jobs, not merely monthly ARPU. Kuiper’s Bac Ninh element is a visible example of this “build here” philosophy. - Competitive discipline

A time-boxed pilot with a subscriber ceiling creates a tournament dynamic. It incentivizes uptime, service quality, rural coverage, and regulatory compliance over raw sign-ups.

Execution risks (for both Kuiper and Starlink)

- Permitting and site rollout: Six gateways imply real estate, power, spectrum coordination and cyber controls. Any slippage risks missing Q4/Q1 targets where political timelines matter.

- Supply chain & integration: Terminal localization is attractive but requires component import regimes, testing labs, and after-sales networks. (In practice, expect initial volumes imported while lines ramp.)

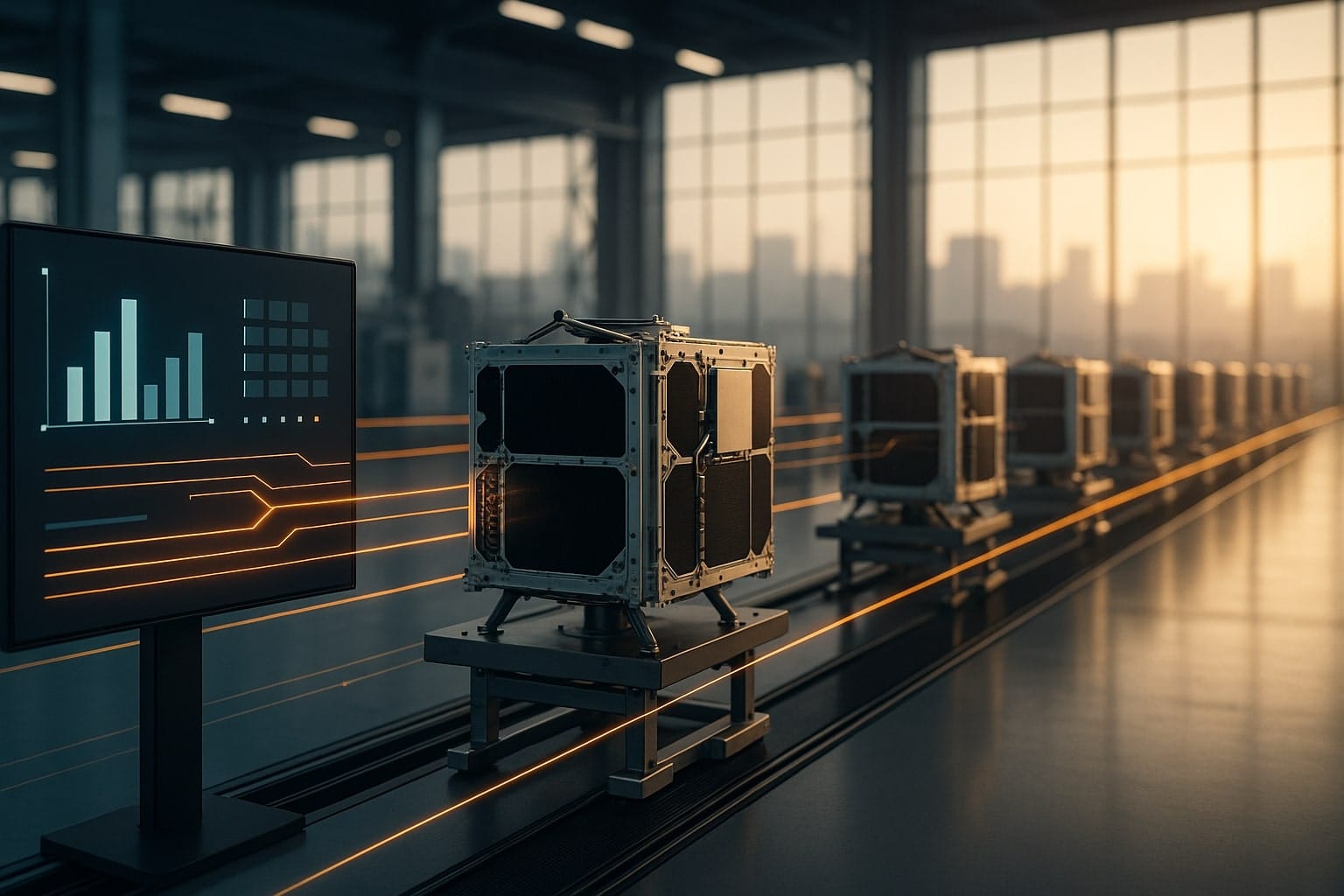

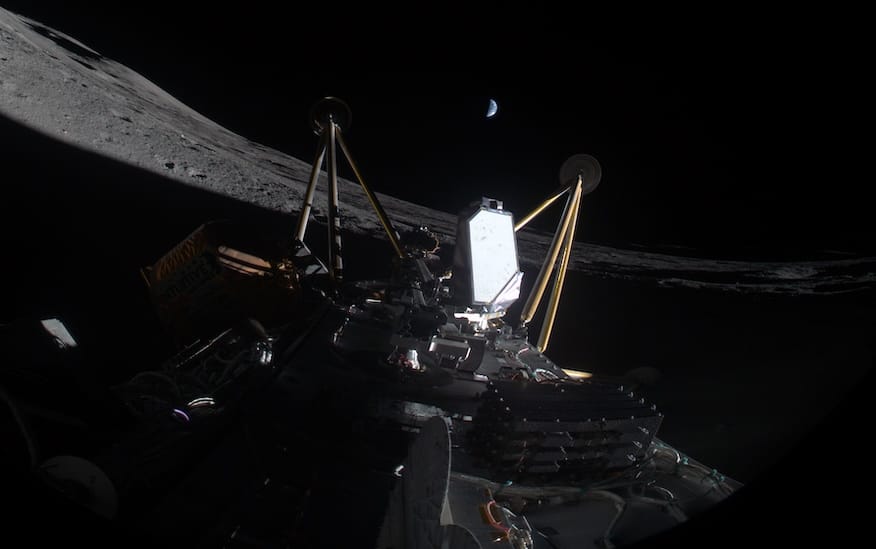

- Constellation cadence: Kuiper is still building out its fleet; it launched its first 27 production satellites in April 2025 and needs steady cadence to support service quality at low latitudes. Starlink’s scale helps, but gateway routing and local entity setup are gating factors in Vietnam.

- Data, identity, and shutdown obligations: Decree 163 and related rules will test operators’ compliance plumbing—from user registration and quality declarations to emergency cut-offs and interconnection. Getting this right early is a competitive advantage.

The regional lens

Vietnam follows Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia, which already allowed Starlink—often positioning LEO as a public-service tool for health and education before broader consumer push. If Kuiper uses Vietnam as a manufacturing + gateway hub, it could seed a Southeast Asia terminal/export base, creating a two-horse race across the archipelagos and highlands of the region.

What to watch next (near-term reporting checklist)

- Licences and entity filings: Has Amazon Kuiper Vietnam Co., Ltd. received all business and spectrum permits? Has SpaceX completed its investment registrations and subsidiary setup? (Both are prerequisites to switch on the pilot.)

- Gateway sites: Where do the first gateways land (North/South)? Are they single-vendor or carrier-neutral? Any co-location with telco data centres?

- Carrier partnerships: Which of Viettel, VNPT, FPT formalize commercial agreements as required by Decree 163? Are there tender documents or MoUs?

- Vertical pilots: First wins in telemedicine, education, maritime, offshore energy, border posts will tell you where the state wants impact fastest.

- Pricing architecture: Do operators launch retail or wholesale-first (backhaul)? Any regulated price guidance or VAT relief for remote-area deployments?

Bottom line

Vietnam is not swapping fibre for satellites; it’s stacking them. A five-year, tightly governed pilot turns LEO into a utility-grade layer for the last-mile that fibre and 5G struggle to reach—while pulling in foreign capex and manufacturing. Starlink brings scale and ASEAN proof points; Kuiper brings industrial localization and Amazon’s cloud adjacency. The winner will be the one that translates policy fluency and local build-out into reliable, compliant service—and proves that LEO can pay its way not just in households, but in the nervous system of the state.